|

|

|

|

Fig. 1. -- TRAINED ASH TREE. ROYAL BOTANIC

SOCIETY, LONDON.

|

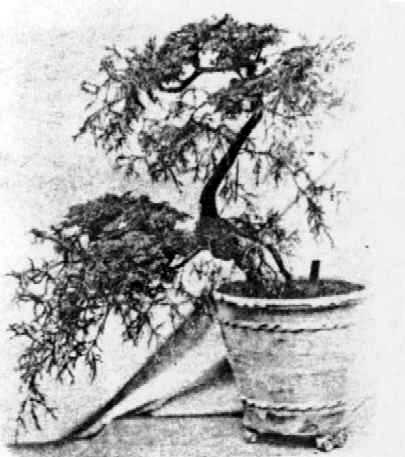

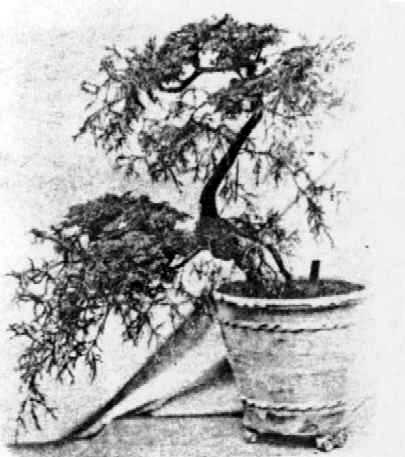

Fig. 2. -- CHABO HIBA (CHAMÆCYPARIS BREVIRAMIA).

|

Fig. 3. -- SHAPED TREES IN AN ENGLISH GARDEN.

|

First of all, I should like to

show you a photograph of an ash tree trained into an arbour in the grounds

of the Royal Botanical Society, Regent’s Park [Plate I., Fig. 1].

The arbour interests me specially,

because of the training of the gnarled trunks; they come down from either

side to meet and intertwine. Abundant leaves flourish over them.

It is practical also, for one can sit down under that shade and take afternoon

tea with friends. This love of rustic decoration and countrified

effect in the centre of the metropolis is much to be admired. It

shows love of the country and of homes in the country. But yet we

know that what is done beautifully for its own sake, and what is done beautifully

for the sake of utility, are quite distinct one from the other.

In the next illustration [Plate

I., Fig. 2] we have an expression of dignity, gravity, and stability.

The tree is commonly known as Chabo hiba, the botanical name Chamæcyparis

breviramia. Its foliage is made up of tiny triangular scaly leaves,

and its massive green enshrouding a rock suggests the stolid power of individuality.

Evidently that is the idea of the artist.

The Japanese artists have this

peculiarity in their reproductions of nature: they minimize the actual

size of the models instead of magnifying it, and the conclusion is easily

drawn that their work is apt to be more often pretty and fascinating than

dignified and imposing. But the effect of this little plant will

upset that commonly alleged theory.

The height of this araucaria with

its pot is no more than two feet and a half.

|

|

|

Fig. 1. -- GRAFT OF CHABO HIBA AND HIYOKU HIBA.

|

Fig. 2. -- CHABO HIBA (THUYA OBTUSA NANA).

|

The next illustration [Plate II.,

Fig. 1] is of a chamæcyparis, but two different varieties

are engrafted together. It measures over three feet, and stands rather

tall for a dwarf tree. Please notice the graceful boughs of Hiyoku

hiba mingling with the clusters of leaves of the ordinary Chabo

hiba. This is effected by whip-grafting. Hiyoku hiba

is the stock, and Chabo hiba is the scion. The whole thing

thus produced is rather different from either of these viewed separately,

and one would be inclined to think it imitated a weeping willow.

Now we shall pass on to examine

some of the constructions of these branches – perhaps I had rather say

the training of them. There never existed in this branch of art such

technicalities as in Chanoyu, commonly known as tea-ceremony, and

sometimes called the tea-drinking cult, although in treatises upon landscape-gardening

we learn a great many hard rules. But the cultivation of miniature

trees is more common in practice than any of the tea cults just mentioned.

It is vulgar, while they are sacred. One might almost say it is well

appreciated by “the man in the street,” and is therefore of peculiar interest

to us.

The Chabo hiba in the next

illustration [Plate II., Fig. 2] is the result of rather rude and severe

manipulation. This form of an upright trunk is seen quite as often

as a gnarled one in miniature trees. The stout trunk of the tree

is often not amenable to the arts of the artist gardener when he receives

it; so it is sometimes expedient to cut it off at the height required;

but often it is left untouched, and in other cases submitted to a skillful

grafting by approach – that is, a grafting effected by bringing a younger

tree to the point where it is required, and the roots of it are sawn away

when the operation is completed. This method is known as Yobi

ki, “a tree sent for.”

|

|

|

Fig. 1. -- CHABO HIBA (THUYA OBTUSA NANA).

|

Fig. 2. -- THE SAME (REVERSE SIDE).

|

Next [Plate III., Fig. 1] we have

quite a different style of training from those which have been described.

The tree has here been severely handled, for the stem is twisted and bent;

evidently it was a young tree when it came under the supervision of the artist.

A comparison of its back [Plate

III., Fig.2] will give an idea of how its branches have been unsparingly

bent and twisted. In this picture, the vigorous bends and twists

of the twigs will remind one of smashed and mingled coils of the spring

of a broken watch. They are, however, all original branches, and

no grafting has been effected in any way.

If we examine closely, we find

what deliberate care is taken in all these bending, twisting younger branches.

The possibility of life and health in a branch, such as will be required

to work it up, or rather conform it to an ideal, is the first principle

of this kind of art. Only by trying it can one understand and appreciate

the difficulties there are to face, for every branch has its own habitual

growth, direction, and power of growth, and, finally, the possibility of

its future; all these factors must hence be taken into consideration.

The result is not one that can be obtained immediately. This bending

operation is usually performed in summer. One of the London journals

made a remark to the effect, “the pigmy-tree business hardly holds out

prospects enough for the next generation but one, for us to invest in it,

but perhaps the Japs think differently. Just fancy, this example

of living patience in the shape of a fan or a saké bottle

being sold in London, for half a sovereign! Enough to break the maker’s

heart, isn’t it?” It seems to me that the man who wrote in this way

must have been a true incarnation of the cast of people so often called

practical

men, whose aim is to be but a stout ledger and calculating machine

in frock coat and a silk hat.

[Grafting]

In the cultivation of miniature

trees there is one very important item we must not overlook – that is the

grafting. I have said a little about it just now. We will take

a Chaba [sic] hiba as an illustration.

There are many kinds of graftings very extensively applied to cedars.

To contrive that such a mass of foliage in compact forms shall be artistic,

it is evidently necessary to adopt and add fresh shoots where required.

Trees grow in their own way, and gardeners must bring them round to their

ideas, so these means are resorted to. The general practice of side

grafting is carried out about March and April, when the new buds are soft.

First you must cut the graft in an oblique manner about one-eighth of an

inch, and then sharply cut again just a little of the outer bark; cut the

stock also at the same angle about a quarter of an inch, and take out the

free portion of bark, and then place the graft in the appointed situation;

tie it once with a soft straw, and then apply a bandage. The introduced

branch must be no more than one inch and a half in length. When the

whole operation is finished, take it into a dark room for some thirty-five

to forty days, and then put it under a straw cover in the open air for

thirty days or so. After that it may at last be exposed without covering

to the open air and sunlight. The reason for avoiding the sunlight

at first is evident. The sap should not circulate too violently when

the joint is just made, until it can be distributed with equal force into

the other part of the tree. These operations are all beyond me to

describe minutely, for it is a delicate business, and needs careful handling.

These who wish to know will only learn well after some sad experiences.

Next we shall see how the pines

are treated. The graftings and bendings here are sometimes similar

to those performed on cedars. Yet at the same time the operation

is much simpler, for, among other reasons, the growth, and naturally the

flow of sap, are much more vigorous than in the preceding examples, and

the twigs do not crowd together so much. The pines are symbols of

bravery, while the cedars correspond to the idea of what is lovable.

The methods of training, and therefore of appreciation, must in consequence

be respectively varied.

Grafting is met with less frequently

where the growth is quicker and the younger twigs can be bent in a wavy

manner. The vertical undulations are called Tatenami, and

the transversal Yokonami. When the leaves do not grow densely,

there must necessarily be some methods used to make the appearance

of the tree more compact. A zigzag line of trunk is widely adopted

in pines. The younger shoots in every alternate concave curve are

nipped away, for the simple reason that they would be hidden from the sunshine,

and the development, therefore, generally unsatisfactory. But the

existence of such shoots is desired sometimes for bringing them out in

different planes and angles. They are called Futokoro yeda,

and may be translated as “pocket branches.” The shoots on the apex

of the concave curve are cherished and nurtured.

Pines have a tendency to shoot

out a set of branches from certain points. These points are treated,

when the bending into zigzag manner is carried out, in early summer, in

such a way as to form the sharpest points in the curves. At that

time all the useless branches are cut off, and the “pocket branches” done

away with. Such, for instance, are Kannuki yeda, the “bolt

branches,” so called because two sister branches spread out from the opposite

side of the trunk at right angles on the same plane [“bar

branches”]. This growth is to be avoided unless the trainer

can see any utility later on. Other forms are the Hasigo yeda,

“ladder,” which has three or more branches forming regular steps as in

a ladder, and the Ikari yeda, “anchor,” which has three younger

shoots at equal distances and curved as in the classical form of the Japanese anchor.

The last-mentioned “anchor” form

is very often adopted at the top of the tree, or rather the younger part,

because the chances of changing the whole shape are multiplied, and the

risk of failing to realize a preconceived design is proportionately lessened.

|

|

GOYO MATSU (PINUS PARVIFLORA)

|

A typical specimen of a well-trained

pine is shown in the illustrations [sic],

Plate IV.

In pines we seldom see grafting,

but sometimes compound growth with young maples; but these are very difficult

things to manage, and fine examples are very seldom met with. Pine

and maple are also wedded together; the green, and the golden or crimson

foliages are not altogether a vulgar composition, but the arrangement of

quantity and position of colours depends on personal artistic taste, and

some of these compositions are very distasteful to an æsthetic spectator.

|

|

Fig. 1. -- A WELL-GROWN TREE.

[Not otherwise referenced in the

article.]

|

Fig. 2. -- SPECIMEN OF NEAGARI,

"ROOT-LIFTING" (GOYO MATSU:

PINUS PARVIFLORA)

|

[Neagari: exposed roots]

We generally come across, whenever

we visit an exhibition of these dwarf trees, one peculiarly trained root

exposed high above the ground. It is termed Neagari; that

is, “the root uplifted.” This is the most difficult of all to appreciate.

Here the gardener’s ideal is carried to the highest and finest point.

The example [Plate V., Fig. 2] reminds one of those solitary pine trees

dotted here and there amongst the hills in Japan as landmarks for pious

pilgrims.

|

Fig. 1. -- SPECIMEN OF NEAGARI, "ROOT-UPLIFTING"

(Akamatsu: Pinus Densiflora)

|

The uplifted roots are the main

object in this training; they look monstrous or ornamental, whichever you

like to call them [Fig. 1]. It is a theory, sometimes, and in some

places much in favour, that things artistic must be copied within proper

limits from the products of Nature that we see and experience frequently.

But the pines with their roots so exposed form an argument against this

favourite theory. Why should not the application to Nature of a preconceived

idea equally deserve the approbation of the highest critic of art?

The pine is such by its nature, as we always see; its foliage is not clustered

in masses, but widely separate. Something was needed to fill the

blank space. Besides, Nature, if I may say so, authorizes the gardener

to dispense with some of the roots in his pot, since the fibrous or hairy

part of the roots is only required for absorbing the nourishment, while

such as are exposed above the ground serve only to ensure the upright growth

of the tree. These are obviously not required in a little pot.

[Watering and soil mix]

Lastly, we must know how to look

after these trees. When we have secured a treasure, we must take

care of it. The dwarf trees should be watered from January to about

June at midday, when a little water may be sprinkled on the leaves; from

June to August, at about two to three o’clock in the afternoon; after August,

at the same time as in the spring. However, the quantity of water

depends upon atmospheric dryness; it is very difficult to fix how many

drops should be given to each pot. The mould contained in the pot

and the nature of the tree must also be considered; for instance, conifers

require little water when in pots. It is better to use the smaller-sized

pots for pines than those that seem to be large enough, for they prefer

dry mould. In potting them, therefore, it is desirable for gravel

to be put in the bottom of the pots, to let the water run through easily;

the mould laid on the top of the gravel should not be a heavy sort, nor

be pressed down tightly. The quantity of water to be given also depends

a great deal on what sort of mould they are planted in. Generally

speaking, the evergreens do not require so much water as the deciduous

plants, which should be habitually kept in a sufficiently damp condition

to let the sap flow in a gentle manner. This last consideration is

very important, for the sap must not be overloaded with water, either when

they are pruned, grafted, or, as is specially the case with pines, handled

so unsparingly by a process generally known as “rings” – that is, the fastening

up of young shoots in a calculated twist to an older branch of the same

tree. Besides the nature of the trees, we must take account of the

local atmospheric condition. Out-of-doors the weather and temperature

vary from one season to another; indoors or under glass they do so only

to a small extent. Finally, the size, shape, and make of the pots

must be considered. It is well to bear in mind that the water, like

domestic medicine, must be carefully administered. In this country,

where so much holiday-making is in vogue, and, indeed, is considered one

of the necessary privileges of the rich, your gardener may go off on a

summer’s day to see his cousin, and find on his return your Chabo hiba

in a drooping state from want of water. He should, in such a case

as that, take this plant straight away into the shade and begin to water

it by degrees; he must satisfy the thirsty tree little by little; let him

remember the fable of “The Thirsty Pigeon,” and say, “Zeal should not outrun

discretion.” [A century later, John Naka teaches

the same care for a briefly underwatered bonsai.]

[Hardy plants]

From the foregoing statements,

you may gather that the cultivation of these dwarf trees requires constant

supervision, and can only be entrusted to competent gardeners.

The general principle of nurture

is as depicted. But every one has his own way of giving water, manure,

and sunlight, and it only shows the dwarf trees are very hardy – indeed,

hardy enough to survive almost any treatment, unless it is overdone.

So the story runs of MIDZUNO Genchusai -- a famous

author who wrote about the cultivation of dwarf trees. Seeing such

a diverse method of attending them, he once asked Ichigoro, the gardener

of HIRAGA Gennai, how he managed to prosper in his

profession. Ichigoro welcomed the author with a smile, and said,

"Why, Nature knows and does her work far better than I. If anything

is the matter with the potted trees, they are pulled out and thrown [planted]

into the grounds. I take no heed of what may follow. The frost

may freeze, the raw wind bite to the pith, yet the zephyr will one day

play her tune upon the outcast plants to recall their energy in company

with the verdant meadows and fields." The author went home and took

the advice in good part; he dismissed all the earlier part of his manuscript

containing the fruits of his experiences of long years, which he now found

to preach quite a useless exercise of anxiety. He may have been reminded

of an old proverb -- "Spare the rod, spoil the child;" at any rate, his

book, when it appeared, displayed a firm conviction that the amateurs could

do their work as well as professionals. The book is entitled "Somoku

Kinyoshu," and from it I gathered much valuable information.

[Repotting]

We must take note of a few important

points as to changing the mould in the pot, which naturally must be exhausted

after feeding the roots confined in it for some time. When the mould

is changed, the fresh nutriment in it will give a sudden impetus to absorption,

and the consequent overflow of sap causes the trees to grow out of their

beautiful shapes; so the greater part of the hairy or fibrous roots have

to be cut out. This is, plainly speaking, to avoid the melancholy

effect of indigestion. To evergreens the fresh mould is given once

in every three years; to the deciduous plants once a year. In both

cases, late spring is thought to be the best season for changing the mould.

The more sandy and lighter mould, with a little mixture of ordinary manure,

is chosen for hard-grained trees; the darker clayish mould will not meet

the requirements of such trees that are habitually given a more frequent

supply of water, as it is more evaporative.

[Some history]

Next, as to the history of dwarf

trees. Some of them are said to be of great antiquity. If so,

this quaint art of training trees must be a very old practice. The

art connoisseurs and collectors generally draw from all sources the best

and oldest works of art. But sometimes things are collected and admired

only on account of being wrought during the reign of King So-and-so; no

matter what they are. For the purpose of historical researches, the

value of an Art Museum should be in proportion to its contents, but there

is not the least doubt [!] one would prefer

paintings on the walls of Burlington House to the frescoes consecrated

to the memory of an Egyptian king of an ancient dynasty. The influence

of age upon the value of a commodity is well known to be an important element.

But true art-lovers should not fail to appreciate their intrinsic value.

I would, therefore, fain dispense with discussion as to the ages of these

dwarf trees, and only mention my authority that potted trees are said to

have been general favourites since the time of SAKAKIBARA

Juda, who introduced [sic] the cultivation

of trees in pots somewhere about the end of the Kioho and the beginning

of the Genbun (viz. in the European calendar, the beginning of the eighteenth

century). But it seems rather doubtful whether this be the true date,

when we remember that the curious tea ceremony and the peculiar style of

garden-making originated as early as the thirteenth century. The

trees in the garden of this school were very likely trained in much the

same style as we see them in pots to-day. Again, we see some pictures

of potted trees drawn by Chinese artists over two hundred years old.

Hence I regret I can offer you no more than a conjecture that the practice

of potting trees was very likely learned from China early in our history,

and has undergone some changes on Japanese soil. Later on, it appears

to me that the schools of flower arrangement in various ways have affected

the cultivation of potted trees. But how far this is so I could not

ascertain at present, principally owing to the scarcity of references at

my command, and the short time which I had to prepare this paper.

In conclusion, I should like to

add (if I may do so without exceeding the generous limits of your patience)

how these miniature trees illustrate the character of our people. It is

evident that we can enjoy and dwell upon abstractions, though the traces

of this quality seem, especially within the last few years, to be on the

wane, being displaced by the more urgent necessity of turning out dynamos

and setting up boilers or engines. But what the Japanese are in heart

is reflected in their pastimes. Recreations tend to be mental rather

than physical, and our people enjoy more or less the same reputation in

this respect as the rest of the Asiatics.

I remember having spoken, in the

introduction to this paper, of paintings, which formed an idealistic contrast

to those of the realistic school, and now, in conclusion, though it may

seem scarcely germane to the intention of this paper, I may add a few remarks

about them. To do that we must go back a while to the masters from

whom the art of painting was learned. In the Sung Dynasty of Chinese

history we first meet “poem pictures” of WANG Mo-ko.

These are very peculiar pictures by an artist who was properly called a

Transcendentalist, since he simply sought the expression of emotions and

conceptions: in every case Nature only plays a subordinate part.

They are, perhaps, too original and too independent. They who painted

them took them from the imagination and from the models which Nature supplied,

as suggestions for developing expressions. The so-called “truth”

that Ruskin delighted in is almost entirely disregarded; in fact, such

pictures are like rhymes and stanzas of the artists who paint their thoughts

instead of imprisoning them in metres and syllables. This imaginative

school is an atelier, where the pupils all study such applications of the

strokes of brushes as are thought best suited to their purposes.

It is more like a child learning how to write out his thoughts in an established

method of writing. The painting is a mere means to transfer the ideas

of one to another. Indeed, when Eastern imagination comes into play,

many an original artist records his name on the rôle of human

achievement. But it often happens that his masterpiece is thought

absolutely impossible, and put away with a sneer by his European comrades.

Still, the racial philosophical temper, which is developed to the highest

pitch, is instinctively inclined to welcome and admire him in his native

land; it is only in his own country that he is understood. So we

understand that other school of painters, who, as copyists, painted whatever

beautiful things appealed to them. They put into their pictures what

they saw. They love Nature, and try to improve on Nature in their

daring designs. These two schools have come to Japan, and are there

still.

[Bonkei]

|

|

A MINIATURE GARDEN (BONKEI).

|

In the cultivation of our miniature

trees, it seems to me that these two schools of painting come together.

Need it be mentioned here that the influence of the idealistic paintings

had a great influence upon the gardeners in forming the shapes of their

trees? Now, the gardeners in Japan are keenly sensitive to the beauties

of the trees in Nature, but at the same time they exert all their art,

whilst copying them, to try and excel Nature. And how their humour

and ingenuity succeeds in the result! The Bonkei – miniature

landscape [Plate VI.] – is the highest development [sic]

in this industry of the cultivation of dwarf trees. The idealistic

painting is indisputably the foundation of the Bonkei. Their

peaceful recreation and gentle refinement may, as is often anticipated,

vanish away before the tyranny of economical competition, which is called

modern civilization. This point I cannot here discuss. But

they have happily established in the pages of Art-history their claim to

be artistic; they may not have been either thinkers, or scholars, or travellers,

or inventors, but they were artists who cultivated such a tree. And,

though we must understand before we can admire and sympathize, I have every

confidence that the world will admire them more in proportion as it understands

them better.

|

|

PINE AND ROCK.

|

The Paper was illustrated

by lantern slides, and several interesting and beautiful specimens of the

dwarf trees were exhibited.

After the reading

of the Paper, the CHAIRMAN thanked

the Lecturer for having prepared, on short notice, so excellent and interesting

an account of dwarf trees, and said he knew he expressed the thoughts of

all present when he marvelled at the skill with which our language had

been handled by a member from Japan. He trembled at the idea of what

would happen if a British member of the Society were called upon at such

short notice to read a paper in Japanese! He then asked Mr. Osman

Edwards, M.J.S., to propose a

Vote of Thanks, which that gentleman did.

Mr. ALFRED

EAST, A.R.A., M.J.S., who seconded

the Vote of Thanks, said that the subject of the Paper had interested him

very much. He well remembered having seen those little gardens in

Japan which gave the impression of being so much larger than they were,

and he had wished to know how the effects were obtained. He came

there that evening hoping that he might perhaps learn something of the

technical processes by which the dwarfing of trees was produced.

He had heard of the grafting of the branches on the stem, and of the pruning

of the roots, but unfortunately he had never had the opportunity on the

spot of learning what he wanted to know, and he was a little disappointed

to-night that the lecturer had not gone further into that part of the subject.

Mr. East went on to say that they must not run away with the idea that

Japanese trees were all small, and he alluded to the well-known magnificent

avenue of cryptomerias at Nikko, which contained some of the largest trees

in the world.

Mr. MICHAEL

TOMKINSON, Member of Council,

supported the Vote of Thanks, and said that no adequate idea of the beauty

of dwarf trees could be got from seeing them grow in London. It was

his opinion that the great fault of English growers in the treatment of

conifers was that they gave them too much water; while as to bamboos and

deciduous trees, he thought they probably did not get as much as they required.

The motion was then

put to the meeting, and passed unanimously. 1 |