February and March of 1969 saw the second ABS tour of Japan, led by Lynn Alstadt

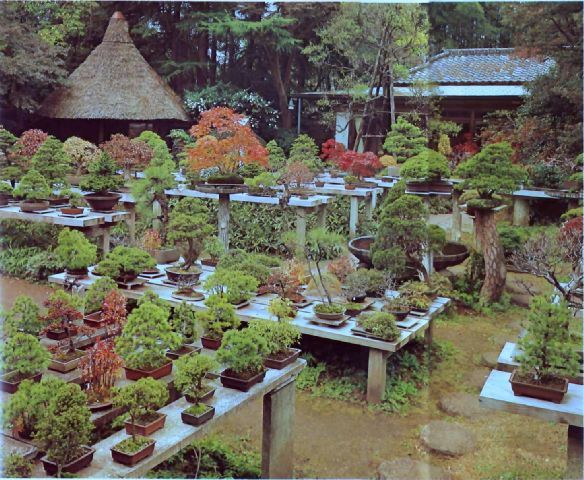

and Jerry Stowell. After touring Takamatsu, Kyoto, and Nagoya, a five-day stay with Kyuzo Murata was further

highlighted by visits to the nine other prominent bonsai nurseries in Ōmiya and the opportunity to see the

prestigious annual Kokufu-ten Bonsai Exhibition in Tokyo.

8

The March 1970 issue of Science Digest contained a reference to Murata and showed BBG

director Dr. Walter Avery with a 21" tall Japanese white pine from Murata's nursery. There were also images of a 150-year-old Chinese juniper and a

93-year-old trident maple (gifted from the City of Tokyo to the City of New York) -- again, from Murata. Then, an early

November issue of the New Yorker magazine noted the arrival of the celebrated three foot tall tree "Fudo" to the Brooklyn

Botanic Garden. The page and a half long article was appropriately titled "Old Juniper."

Considered to be between 600 and 1,000 years old, the tree was reportedly found in

1910 by the famous bonsai tree hunter Tahei Suzuki

and was first wired by Kinsaku Saida, said to be the greatest wiring master of all time. Making its first public

appearance in 1929, the bonsai received the first prize -- and promptly vanished. Its owner at the time was a

Japanese oil magnate who was afraid that exhibitions would spoil the tree. A special place deep inside his

mansion was built for the "Phantom Shimpaku"

(as it would be called by people who saw the tree during its only exhibition).

|

|

'Fudo alive and well in 1935 at the 13th[sic] Kokufu-ten

bonsai exhibit in Japan.'

(Probably 3rd if 1935, otherwise 1940 if indeed 13th)

(https://imgur.com/gallery/WqRon)

|

From pg.

88

of the article "Japanese Miniature Trees," Life, October 7, 1946

about Keibun Tanaka's

20-year-old 5,000-tree collection in suburban Tokyo, this picture of what we would know as "Fudo."

Has the

erroneous caption of "300-YEAR-OLD PINE TREE IS VALUED AT $2000."

(The image in a copy of an article long in our

files was brought to RJB's attention again

by Roberto Pagnin, Italy, 27 May 2008 in personal e-mail.

This copy

gotten from Google's Life Magazine photo archives at

http://images.google.com/hosted/life/1d30469dca4234bd.html.

Photographer is listed as Alfred Eisenstaedt.)

|

In 1946, having survived the war, the tree was purchased by Yoshimatsu

Hattori and received the name of

"Fudo." The name comes from the

"God of Fire Fudo," an imaginary guardian of the Buddha against all evils, standing amid burning flame

without moving. "Fudo"'s appearance suggested swirling flames.

Yoshimatsu Hatori died in 1960, and his entire bonsai collection was put up for

sale, except "Fudo" which was taken by his son Osamu. Although Osamu was not keen about bonsai, it took Kyuzo

Murata several years to persuade him to sell that particular tree. It was finally in the summer of 1969

that "Fudo" came to Murata at Kyuka-en, by which time not many people had actually seen the tree except in a photograph.

Per Dr. George S. Avery, director of the BBG who was instrumental in introducing

tens of thousands of Americans to bonsai and in developing the Garden's outstanding collection:

"[This tree] was first seen by Botanic Garden representatives in

November 1969 when a tour group of garden members visited the Murata Nursery, while in Japan.

After admiring many of the trees available for purchase, two members of our group kept wandering back

to look at a gnarled and twisted "old timer," a

shimpaku

(Sargent juniper). To see it was to read at a glance its autobiography -- lonely centuries of a

frugal existence in an out-of-the-way mountainous region somewhere in Japan, buffeted by continuous

winds and winter storms, but always with the strength to survive. The tour member whose gift

made possible its ultimate purchase prefers to remain anonymous, but as a Botanic Garden trustee she

has long-admired and appreciated fine bonsai.

"A few days after the visit [it was decided that the tree] ought to be

[sic!]

in the Botanic Garden's bonsai collection...and, through a Japanese friend, we telephoned Mr. Murata

the next morning, reporting probable interest in acquiring his tree for the Botanic Garden. He

was noncommittal but said he would mail a photograph of the tree, to reach us after our return to the

United States.

"In December, the photograph arrived. A letter was promptly

dispatched from the Botanic Garden to Mr. Murata, accompanied by a purchase order for the tree.

No acknowledgement was received so in the ensuing weeks other letters were written [in English and

Japanese]. It seemed that we had failed (or were failing) to convince Mr. Murata that the tree

should come to make its life in America...

"In early July, 1970, a beautiful letter arrived from Mr. Murata.

[It expressed his sincere apology for not responding earlier. He had had to travel to Osaka

several times to set up the Bonsai Show exhibit at EXPO '70.]

[When people found out that Murata was contemplating sending the

shimpaku

to America, they tried to persuade him to keep the tree, but at long last he decided not to. As he

wrote in his letter to the BBG,]

"'Personally, I do wish to keep this fine tree in my private

collection as long as I live; but since I am in the trade, I am willing to sell it only if some

vital qualifications are met. Recently, air pollution in Japan is becoming unbearable for both

human beings and especially for trees in the garden. The pollution is caused mostly by motor cars.

I am not against progress, but trees do not understand it. They just have to suffer and sometime die

quietly. I have been told that Brooklyn Botanic Garden is large enough that it cannot possibly have

a pollution problem within its premises. There is no place in America like the Brooklyn Botanic Garden

where all necessary facilities are available for proper care. Above all, it is highly important that

American people, most of whom are still relatively strange to our fine art of bonsai, will have a chance

to appreciate the tree.

"'These were a few of my many reasons, and at the end everyone [to

whom I explained my reasons here] understood. I have said to my friends that I would not sell it

even for a million dollars, if the Brooklyn Botanic Garden were a commercial nursery; but I know BBG

staff would love and care for my tree, not just professionally, but wholeheartedly. Anyway, it

is all right now, and I feel as if I am giving my own daughter to an American to be married.'"

|

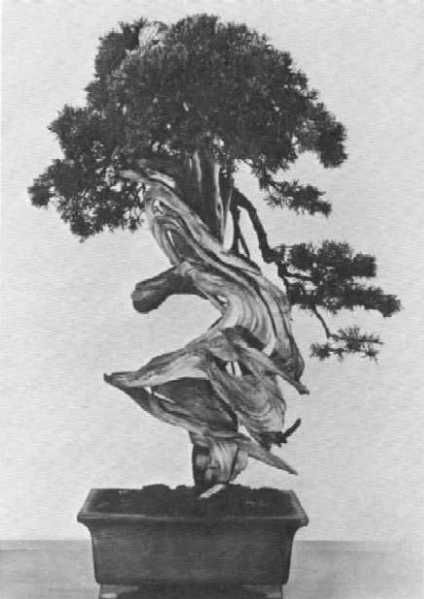

"Fudo" (b&w from ABS Journal article;

color photograph copyright Yukio Murata and reprinted by

permission.)

"Fudo" arrived in New York via Pan American Airways and was officially met at

Kennedy International Airport by Robert S. Tomson, Assistant Director of the BBG, together with representatives of

the U.S. Department of Agriculture. The prescribed fumigation treatment was carried out, and "Fudo" was put

on display at the BBG in a screened quarantine cage, still damp from her insecticidal bath. There she would remain

until released by the Plant Quarantine

Division of the Department of Agriculture. This hardly seemed a fitting wedding reception for so distinguished

a bride; yet it complied with plant importation law and was a justifiable precaution against the introduction of

plant pests which, though perhaps no problem in their original homeland, might be difficult or impossible to control

if they were to escape in a new environment.

9

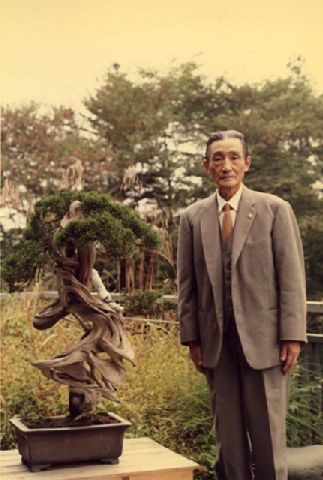

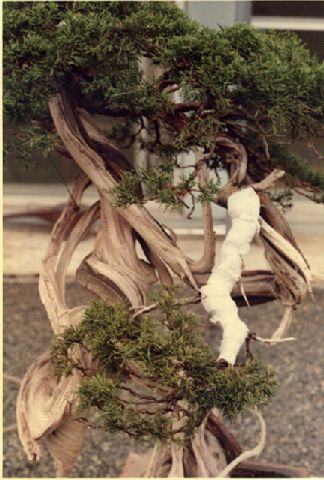

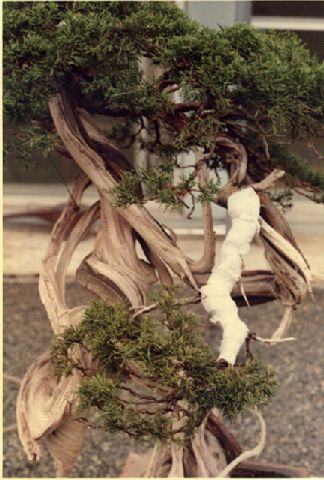

Close-ups of "Fudo" showing protective gauze wrap around weak branch and the magnificent deadwood.

Close-ups of "Fudo" showing protective gauze wrap around weak branch and the magnificent deadwood.

(Copyright Yukio Murata and reprinted by permission.)

The BBG's bonsai specialist, Frank Okamura, was quoted in that aforementioned November 1970

New Yorker article as being "deeply concerned about the strip of gauze, since it indicated the bonsai

had been seriously injured -- possibly during packing. 'You can see that the wood under the gauze is starting

to turn color, and I'm afraid that at least that branch of the tree is dead.'

"We asked whether this could prove fatal to the entire bonsai.

"'I don't think so,' Mr. Okamura said. 'You know, we'll all be watching

it and doing everything we can.'"

In October 1971, the fine shimpaku "Fudo" was declared dead without ever

having become acclimated to its new home, despite extraordinarily special care. Her ancient body with its

unique beauty is still preserved at the BBG where it remains inspirational in a special case in the rotunda of

the Garden's Administration Building. Probably the oldest living plant of any kind ever shipped to the U.S.,

it was said to be about eight hundred and fifty years of age when it died after a year here. A photograph

taken in 1970 in Japan "shows the lower branch, where all the trouble apparently began, not showing any visible

change, but the foliage on that branch was thinner than the rest of the foliage."

"She departed this world leaving many pleasant memories and the love of many

people. I consider that 'Fudo' is still a valuable asset to us all."

(On October 7, 2008 a memorial ceremony was held for "Fudo" at the BBG.)

10

Preserved Fudo at BBG, photo c.November 2008 by ydde72183

Preserved Fudo at BBG, photo c.November 2008 by ydde72183

(Source: http://www.servimg.com/image_preview.php?i=30&u=13511407)

The September 1971 issue of

Shizen To Bonsai (Nature and Bonsai)

magazine contained an article by Murata regarding the early days of ezo spruce bonsai. (The article would be

translated into English, edited and reprinted nineteen years later in

International Bonsai

magazine.)

And on October 3 of this year Isamu and Rumiko Murata welcomed their son, Yukio, into the world. "At that time,

Mr. William Valavanis [later of

International Bonsai

fame] was living in Bonsaimura and he [would later tell] me that he remembered how excited my mother was to show me

to him," Yukio would later recall. The Muratas already had a daughter.

11

In November, 1971 a Workshop and Study Tour of Japan took place, endorsed by

the ABS. Lynn Perry Alstadt, Constance Derderian, George Hull, and Jerry Stowell led the tour which featured

a four day seminar at Murata's Ōmiya garden.

One year later, Luther and

Dorothy Young led a trip with

classes to Japan and Hong Kong. Visits were paid to Kyuzo Murata, Toshio Kawamoto,

Wu Yee-sun, and other hosts and locales.

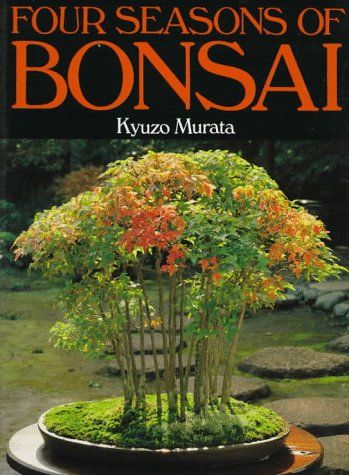

In 1973 Kainan Shobo published a work that Murata surpervised.

Bonsai no Tsukuri Kata (How to Create Bonsai) was written by Nagai Kazuo. Also this year, Kyuzo

edited Ko Katō Tomekichi-Ō 27-kaiki tsuizen chinretsu kinenchō (Commemorative Bonsai Exhibit

on the Occasion of the 27th Anniversary of the Death of Tomekichi Katō), a catalog of an exhibit held at

Manseien on September 20 and published by Shutsurankai.

12

In May of 1975, Kyuzo Murata (left, above) flew to the U.S. to inspect the rare

and valuable bonsai at the

U.S. National Arboretum

that had been given by Japan to commemorate the Bicentennial. (Please see this documentary about the

gifting, Bonsai Fly to U.S.A..)

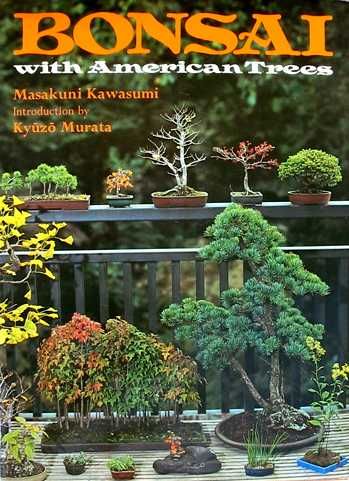

He returned in July with Masakuni Kawasumi (right, above, born in 1923 and successor to his father's now

international distribution business) and four other people from Ōmiya.

Murata visited the Brooklyn Botanic Garden where a gathering of 300 people

heard his talk on the art of bonsai. Quoting from The New York Times,

July 9, 1975: "Bonsai is the art of pruning and wiring branches and cutting roots which eventually result in

controlling growth so that trees are trained to live in pots,' said Mr. Murata. Because Mr. Murata, a

Zen Buddhist, believes that trees have feelings, he said

it hurts them to be cut. 'But it has to be cut,' he continued, 'The tree must understand that I do it

out of love -- it's like spanking my own children

[sic]

.'"

Murata and Kawasumi were the guest artists at both the BCI convention in

Miami Beach, FL ("New Bonsai Horizons," running from July 2 through 6 and attended by 319 people) and the ABS

convention in Kansas City, MO (held July 10 through 12). In Miami, a styling criticism Murata noted was

that the foliage crowns of American bonsai were too full and ill-defined. Murata's closing remarks to

ABS following a wide-ranging overview of "my favorite and the only subject I have known all my life" were:

"Again, I wish to emphasize that bonsai is not a mere sketch of nature but a reflection of the heart of the

creator. Please create your own Americanized bonsai and fill the world with this peaceful art.

Sayonara, I shall see you in Tokyo."

13

|

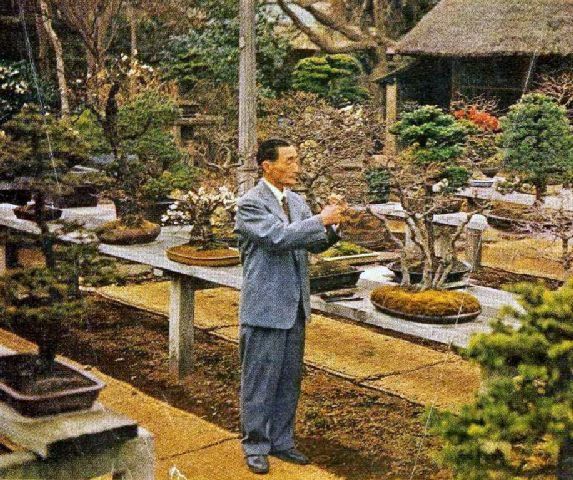

"Yuji Yoshimura with Mr. & Mrs. Kyuzo Murata at Kyuka-en Bonsai Garden, Ōmiya, Japan 1968."

"Yuji Yoshimura with Mr. & Mrs. Kyuzo Murata at Kyuka-en Bonsai Garden, Ōmiya, Japan 1968."