"In that fascinating nightmare, L'Homme qui Rit, Victor Hugo tells

us that in the seventeenth century there existed in Europe a band of nomads, known by the name of

comprachicos, or children buyers, whose special

handicraft was the transformation of their unhappy purchases into dwarfs and monsters for the particular

delectation and amusement of popes and princes. In the nineteenth century, in our own corner of the world,

at any rate, the comprachicos are luckily as obsolete as the rack and the thumbscrew; but the practice of

interfering with Dame Nature in her benevolent occupation of strewing our path with things of beauty which are

joys for ever still thrives in Japan. The daimios of Yokohama and Nagasaki are not content with the

countless beautiful gems of the plant world with which their favoured islands are studded, but they must also

have dwarfs and monsters of the vegetable kingdom. They must have Pine trees with the best part of their

roots leaping up into the air several feet higher than their topmost twigs, or Kakis with their branches so

contorted as to resemble tangled masses of cordage instead of the graceful trees which we know them to be.

In the 'Revue Horticole' for July 16, Mons. E.A. Carrière gives a long and

interesting account of the dwarf and monster plants shown in the Japanese section of the Paris Exhibition.

These vegetable abortions [sic] have hitherto only been known to us through the

medium of the metal and fictile wares of that wonderful country.

|

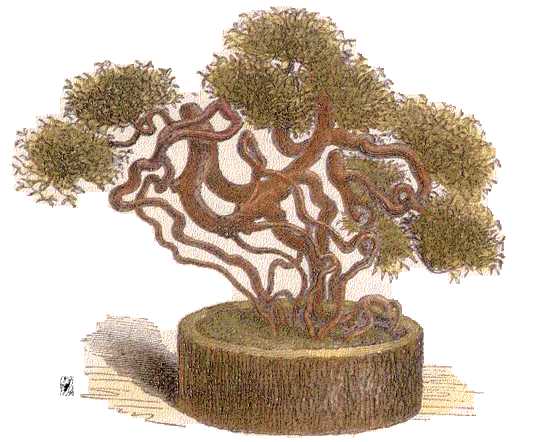

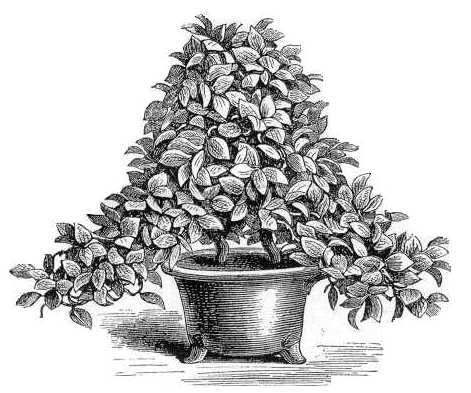

Fig. 1.--Two young plants of Pinus densiflora, deformed.

|

Fig. 2.--Specimen of Pinus densiflora, with the larger

portion of the roots growing in the air.

|

M. Carrière admits at starting that he can only guess [sic]

at the methods used by the Japanese comprachicos for producing these vegetable

monstrosities, which not only include dwarf plants, but also shrubs and

bushes of tender years, which wear a feeble and venerable appearance long

before the natural time. Figs. 1, 2, and 3 are good examples of this

peculiar development of the art of horticulture. M. Carrière

supposes that when the Japanese wish to dwarf any particular subject they

naturally choose those varieties which most lend themselves to being checked

in their growth by various means. By training their shoots, and branches

with the utmost patience, they are able to produce the most monstrous forms,

while by limiting the amount of nourishment which the plants receive within

the narrowest possible limits they become dwarfs. Hence, by adopting

the latter method, of checking their growth, they succeed in producing

plants which, although they may be over a century old, are still small

enough to live and thrive in a medium-sized flower-pot. We must also

remember that the climate of Japan is peculiarly favourable to this description

of horticulture, and it is doubtful [sic]

whether this kind of culture could be carried out in hot, dry, sunshiny

countries. Of all hardy subjects the Conifers seem to have produced

the most successful specimens of dwarfs and monsters, either because they

are more fitted for this mode of treatment, or because they are more in

favour in Japanese gardens. Amongst the Conifers again Pines seem

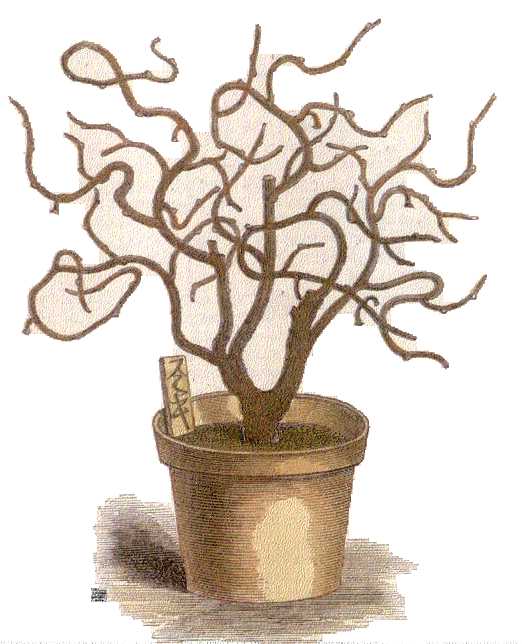

to produce the happiest results. As seen in figs. 2 and 3, the stem,

which is reduced to its very simplest expression, grows at a distance from

the surface of the soil, and is supported by a number of simple or branched

roots supported by sticks, which float about in the air as if they belonged

to it. The results shown in figs. 1, 2, and 3 are difficult to explain,

especially that which, as will be seen, sends up a root from b,

which, bending round in the form of a syphon at a distance of 2 ft. or

3 ft. above the plants, descends once more as far as a, where it

splits into a number of branches, if such a word may be applied to a root,

and descends into the soil contained in the pot, whence it conveys nourishment

to the plant by the circuitous path shown in the cut. In the majority

of cases it is difficult to fix the exact spot at which the root ends and

the stem begins, as they seem to run into each other. If we carefully

examine fig. 3 we shall apparently find that the end of the root-stalk

is at a, and that from thence to the point b, where the cotyledons

formerly existed, the part may be considered the collar, so that below

this point we may still find a portion of the root-stalk, which, becoming

thinner, is easily confounded with the roots properly so called.

|

|

Fig. 3.--Pinus densiflora, submitted to the same

treatment as the specimen shown in fig.2 (1-8th the natural size).

|

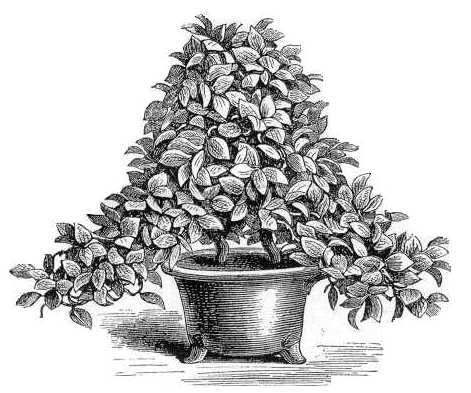

As shown in figs. 4, 5, and 6, the branches and shoots constituting

the head of the tree may be contorted by training into the most extraordinary

dwarf and monstrous forms; in fact, everything is done to prevent them

from growing in a vertical or horizontal direction. This system of

cultivation seems to be very widespread throughout Japan, and must be practised

by a large number of persons, for such specimens as the one shown in fig.

1 are exhibited by hundreds. Worried literally half out of their

lives by ill treatment and starvation, it is not to be wondered at if the

size of some of these unhappy victims are wholly out of proportion to their

age. For instance, the puny-looking plant shown in fig. 1 is ten

years old, while that represented in fig. 2 has seen at least eighteen

summers; and the Pinus in fig. 3 nearly trebles that age. The monstrosity

shown in fig. 4 is thirty-four years old, and the Nageia (fig. 5) is only

five years younger. These ages, it must be observed, are only approximative.

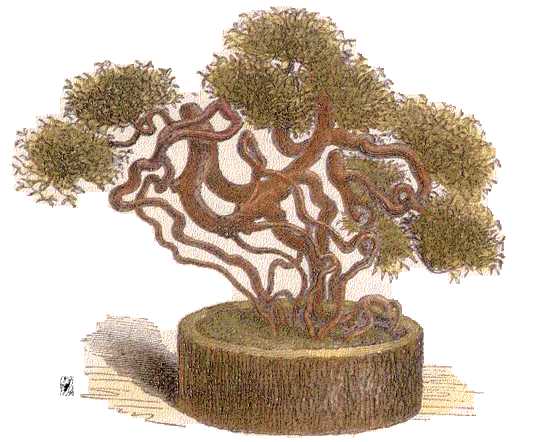

Although the Pines seem to be particularly amenable to this mode of treatment,

there are other members of the family of the Coniferæ which are also

capable of gratifying the perverted tastes of the Japanese aristocracy,

such, for instance, as the Chamæcyparis, the Podocarpus, and even

the Nageia (as shown in fig. 5).

|

|

Fig. 4.--Stunted and deformed specimen of Rhynchospermum

japonicum.

|

It is clear that other species of Coniferæ may be submitted to

the same process with similar results. This peculiarity of the Coniferæ,

no doubt, is caused by the fact of their having excessively long roots,

as any one who has grown Pines in pots can readily testify. Without

positively asserting anything, M. Carrière gives it as his opinion

that the whole secret lies in the choice of subjects with extremely long

roots; and in support of it he instances the fact of a seedling Cedar,

which was sown in heat in a tube containing Moss, out of contact with the

air, and which, in a very short time, produced roots 18 in. or 20 in. in

length. It must also be remembered that as the Japanese do all they

can to check the growth of the aërial half of the plant, the subterranean

portion must necessarily become unnaturally developed. The singular

results shown in figs.1 and 3 lead one to inquire as to whether the effects

are obtained before or after the plants are placed in pots.

|

|

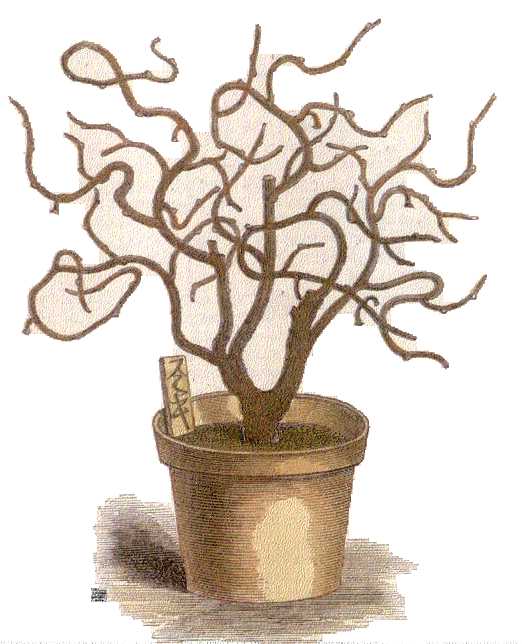

Fig. 5.--Nageia ovata in a Japanese flower-pot, with

the branches growing downwards (1-8th the natural size).

|

Be this as it may, it is perfectly evident that some means are taken

to draw the roots out of the soil gradually, without in any way damaging

the rootlets, so as to expose all their ramifications to the air, leaving

only a small portion of their extremities in the soil. It is not

only in ornamental plants that the Japanese Comprachicos work their wicked

will, for they apply the same system of dwarfing to fruit trees -- first

of all in a natural way, by tying the branches together in such a manner

that they grow inwards instead of outwards; and, secondly, in an unnatural

manner, by excessive pruning, or by checking their growth one way or another.

Judging from the specimens shown in the Trocadero and at the Jardin Fleuriste,

the fruit trees best adapted for this method of treatment seems to be Kakis,

Peaches, Plums, and Cherries. The Kaki seems to be designed by Nature

for the especial purpose of being dwarfed and otherwise deformed.

Some of the specimens exhibited are very dwarf, being only from 16 in.

to 30 in. in height, but they are covered with flowers, and, judging from

the condition of the shoots, they must have fruited abundantly. In

growing fruit trees, the Japanese follow the method adopted by our western

fruit growers, and leave only from six to twelve fruits on each tree, according

to its natural vigour. Another peculiarity of these dwarfed and deformed

trees is that their roots, as a whole, are very small, the subterranean

portions being comprised in a few small tufts of rootlets.

|

|

Fig. 6.--Full-grown Kaki, with the branches deformed

by pruning and training, bearing here and there fructiferous peduncles.

|

It is impossible to say whether this is the result of checking the growth

of the aërial part of the plant or of perpetual transplanting, so

as to keep the subject, so to speak, in a constant state of ill-health.

In the absence of any trustworthy information on the subject, we can only

surmise that both these methods are practised.

C. W. QUIN 1

|