| 21 |

2014 -- Thierry Font died after a long battle with cancer. (Born in France 53

years earlier, he was a level 3 demonstrator, the highest level awarded by the Féderation Française

de Bonsai. Font was a regular contributor to magazines Bonsai Passion (Castilian) and Bonsai

France (French), for which he wrote technical articles and, through his wonderful drawings, managed to convey

to the public details of his technique and the reality of their evolving work. He performed graphic art

studies in Montpellier and for two years (1985 and 1986) made a display in the YAMADORI BONSAI specialist stores

of Montpellier belonging to Gilbert Labrid. Font went on to conduct workshops and demonstrations, participated

in exhibitions with his trees in various clubs in France and in countries such as Italy, Belgium, Spain, Canada, and Brazil. He worked

in collaboration with the Mistral Bonsai workshop since 2002 and in 2004 was invited to Japan by Takeo Kawabe to perfect Font's techniques.

He wrote the blog http://thierryfontsakurama.blogspot.com/. He left behind his wife,

Chantal, and their two daughters, Marine and Anouk.)

("Thierry Font; in memoriam,"

http://www.bonsaicentersopelana.com/2014/04/thierry-font-in-memoriam.html;

"Sad farewell to our friend Thierry Font," Google translation of

http://www.portalbonsai.com/categoria.asp?idcat=676794; "Thierry Font,"

Google translation of http://www.espritsdegoshin.fr/forum-bonsai/topic.html?id=13095&p=1) SEE ALSO: Apr 21

|

||||||||

| 22 |

1957 -- Arthur Joura was born in New York City. [He would have an educational

background in fine art, studying at the School of Visual Arts and the Art Student's League in New York City.

As a landscape-maintenance tech for the

North Carolina Arboretum, Joura would be running a backhoe and building

hoop houses in the garden's support area when, in 1992, the Arboretum received a donation of a large number of bonsai and

containers from George and Cora Staples of Butner, NC. Joura had no experience with bonsai, but he would sense an opportunity.

Upon acceptance of this initial donation, he would be assigned responsibility for the care and development of the bonsai collection and

an attendant program to support it. He would start his bonsai education in 1993 at

The National Bonsai and Penjing Museum in

Washington, DC under the tutelage of Museum Curator Robert "Bonsai Bob" Drechsler. Joura would learn the traditional forms

and the various techniques. He would go to Japan to study the art. In 1995 Joura would continue his studies with

personal instruction from Japanese American bonsai master Yuji Yoshimura, also known

as "The Father of American Bonsai." Later that same year, Joura would begin teaching bonsai at the NC Arboretum conducting educational

classes and workshops as well as providing bonsai lectures and demonstrations across the country. Other donations

to the bonsai collection would follow as longtime enthusiasts in the region recognized the value of the Arboretum's involvement, and

contributed prized specimens from their personal collections. Sustained public support would be a key ingredient

in the success of this dynamic bonsai assemblage which Joura, the curator, would build into one of that institution's

strongest components. Additionally, Joura would introduce to bonsai culture over 50 species native to western

North Carolina and create several tray landscapes depicting well-known regional sites. Perhaps of even greater significance,

the model for the Arboretum's bonsai plantings as Joura styled them would not be the bonsai depicted in books and magazines, but rather

the example of nature as represented by the wild trees of the forests and mountain tops of the Blue Ridge region. Joura would feel

that this was a return to the roots of bonsai as an artistic expression, not of a certain culture, but of an individual's experience

of the natural world around them. For more details on Joura's education, please see

this posting and

this one as well.]

1986 -- The 1st Exhibition of the Korean Bonsai Association (founded Jan. 1985) began and would run through the 17th of May. [Subsequent annual large-scale potted plant exhibitions for growers from all over the country would be called "ceremonies."] (KBA web site, http://www.koreabonsai.com/en/frame.html) |

||||||||

| 23 |

1952 -- Thirty-one year old Yuji Yoshimura, assisted by German agricultural diplomat Alfred Koehn, began the first bonsai

course for foreigners in Tokyo at his Kofu-en nursery. [It was an instant success and within three years over 600

students -- mostly foreign dignitaries, military personnel and businessmen and their wives -- would be taught the

six-lesson course in classical bonsai art.] A tropical plant expert, Koehn lived and worked in Japan for several years in the early 1930s. He studied Japanese flower arrangement in Kyoto for four years before moving to Peking in 1935 to study Chinese arts and culture. While living in Peking during the Japanese invasion (1937-45) he established his "Ra Shi" kennel for Shih-tzu dogs. (In 1948 he was the only breeder of those dogs in the capital.) Koehn left China to return to Japan in 1951 to open courses the following year in the cultivation of bonsai in collaboration with Yuji Yoshimura. His Notes on Bonsai (1953), with hand-tied wraps, two full color plates and four pages of black and white plates with multiple images, was an early work in English on bonsai. Koehn's other publications included The Way of Japanese Flower Arrangement (1937), Japanese Tray Landscapes (1937), Mountains and rivers: woodblock prints from paintings by contemporary Chinese artists (1939), Embroidered Wishes (1943), Confucius, His Life and Work (1944), Kindesehrfurcht in China (1943, then the following year in English as Filial Devotion in China and in French as Piete Filiale en Chine), Fragrance from a Chinese Garden (1944, with Wang Hsiang-chan), Royal Favorites (1948), Window flowers: Symbolical silhouettes for the Chinese New Year (1948), Japanese classical flower arrangement (1951), Bonkei: Japanese Tray Landscapes (1952), "Harbingers of Happiness: The Door Gods of China" (in the Monumenta nipponica) (1954), and Japanese floral arts: Flower arrangements, tray landscapes, gardens (1955) -- among others.

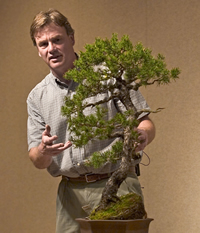

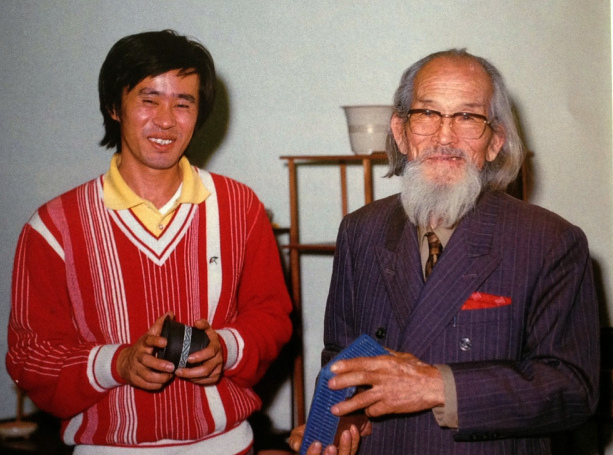

"Alfred Koehn, next to Mr. Yoshimura on his left, is explaining rock planting techniques to

("Yuji Yoshimura, A Memorial Tribute To A Bonsai Master & Pioneer" by William N. Valavanis,

International Bonsai, IBA, 1998/No. 1, pg. 32; "Alfred Koehn,"

http://tiny.cc/70l6l; "Alfred Koehn,"

http://tiny.cc/i5l1j;

http://www.pem.org/aux/pdf/library/Herbertoffen.pdf;

http://tiny.cc/i0x6s;

"A Brief History of the Shih-tzu," http://www.bakalo.com/history.htm;

"Shih Tzu - The Last Shih Tzu To Leave Peking,"

http://www.articlealley.com/article_13784_54.html;

Yuji Yoshimura's collaborator is not to be confused with the German doctor of the same name who lived 1911-1984)

SEE ALSO: Jan 12, Feb 27, Jul 17, Nov 2, Dec 24

Mr. Yoshimura's students in his course in 1952." (Photo by Yuji Yoshimura) (International Bonsai, 1998/No. 1, pg. 33) 1986 - Bjorn L. Bjorholm was born in Knoxville, Tennessee. [He would become obsessed with bonsai after he saw one of the Karate Kid movies when he was 12 and involved with karate. He would ask for his first tree, a little juniper, for his 13th birthday and it would last for a month or so. A second tree, a banyan ficus, would stick around for 10 or 12 years. He would add trees collected from his folks' yard or from the burn pile at the local nurseries, and he'd carry around a bonsai book all the time at school. As a short, chubby kid, he would also play the trombone in the marching band, which didn't help his social status. He, his father Tom Bjorholm, and a few others in the eastern part of the state would found the Knoxville Bonsai Society in 2001. He would help his father maintain a collection of a hundred-odd trees. [Bjorn would be 16 when he'd travel to Japan as part of a student group in a two-week program sponsored by Panasonic, which had an office in Knoxville. There during his many visited places, he would see his first native Japanese bonsai in a small yard. Back in Panasonic's Osaka he would stay with a host-family. Few words were shared but the host would ask him about any hobbies. Mentioning "bonsai," Bjorn would happen to be taken to the nursery of Keiichi Fujikawa the following day. Communicating through the host, Fujikawa would be amused by the American youth's passion for an Asian art form more than a millennium old and jokingly offer Bjorn the opportunity to someday come back as an apprentice. Bjorn would take the comment seriously. He would graduate from Halls High School in 2004 and then college would follow, as would a year of studies abroad. He'd graduate in 2007 from Ritsumeikan University in Kyoto which would have recently established ties with the University of Tennessee. Joining Bill Valavanis' tour for the Kokufu-ten in February 2007 he would act as a partial translator. Approaching his adult 6'5" height, the blond, all-American Bjorn would meet Keiichi Fujikawa at the show and remind him of their previous meeting -- which Fujikawa did not seem to register. Returning to Memphis, Bjorn would begin to email Fujikawa (after the messages were corrected by a friend who was fluent in Japanese). After several missives, the teacher was not pleased with the student-to-be's language and did not feel the young America would have the proper work ethic to accept him. More emails would be sent and Fujikawa would then reply with what would be required to be an apprentice. In the meantime Bjorn would work with a handful of professionals during his frequent returns to the United States. [Eventually a three-month trial period would be arranged at Fujikawa's Kouka-en ("White flower") school and nursery in 2008. Bjorn would have to find his own apartment within bicycling-distance to it and be there only on his passport, not a visa, but he would be provided with rent-reimbursement and meals. Bjorn would be on probation for those 90 days, being the only apprentice at the time and Fujikawa's first. Fujikawa-san would have apprenticed under Saburō Katō in the late 1980s at Mansei-en and his understanding of apprenticeship would come from that experience, a much stricter, less mellow training than subsequent students would undergo there. Bjorn would be forever grateful for that extra discipline which would remove any romantic cultural notions during his first year of Japanese apprenticeship with the best trees and teachers in the world (the time during which many apprentices would quit the process). When Bjorn would first arrive, conversation with Fujikawa would be conducted through "pointing and grunting." Bjorn would become fluent in Japanese, "though some days are better than others." Half-way through the ninety days Fujikawa would agree to help Bjorn apply for the visa. "It's all about the movement of the trunk and the placement of the branches," Bjorn would explain, adding that a bonsai takes decades of subtle shaping and pruning to achieve anything close to perfection. Even then, the work never ends. "People say the only finished bonsai is a dead bonsai -- which you never want to happen," he would continue. "The trees constantly change hands, and that community effort makes bonsai a very special art form. Multiple people will work on the same tree over time, each with a different take on how the tree should be designed." He would style bonsai for the Kokufu-ten, Taikan-ten, and Sakufu-ten exhibitions. His Bjorvala Bonsai Studio website would date from 2008. Bjorn would then be pictured in an article in the Nov. 2010 issue of Kinbon magazine. He would film, edit, and produce the online YouTube video series "The Bonsai Art of Japan," beginning in mid-April 2011. He would go to grad school on a full scholarship for an International MBA in Memphis and Osaka beginning in the Fall of 2010. [He would be one of the North American artists at the 7th World Bonsai Friendship Federation (WBFF) Convention in Jintan, China in late September 2013. In 2014 the 28-year-old newlywed and his Chinese-born and Japanese resident wife, long-time friend Nanxi Chen (trilingual with two masters degrees) who he'd meet at Ritsumeikan, would be living in Osaka, Japan. There Bjorn would continue to own and operate Bjorvala Bonsai Studio, teach at the Fujikawa International School of Bonsai, and would become one of the ancient tree-training art form's most promising and unlikely faces. His apprenticeship would last six years and then he'd stay on three more years working at the nursery, similar to the 5 year + 1 more of other bonsai apprenticeships. During that time he would also complete part of the requirements for an economics Ph.D. at Osaka University. He would travel to the United States twice a year, trips that would be part teaching tour and part maintenance assignment. He would tend trees for several American clients and attend numerous bonsai exhibitions and club workshops. His varied educations in Japan would allow Bjorn to be able to articulate characteristics of the bonsai process previously unspoken of. This international traveler would begin posting his vlogs in mid-November 2016, set up his new website the next year, act as his own translator during a demo at the 8th WBFF Convention in Saitama, Japan that April, and then begin his Bonsai Network Podcasts in early January 2018, with the announcement that he and "Nancy" (Nanxi) having returned to the U.S. had purchased property in Tennessee on which to build his studio and Eisei-en ("Forever green/young") nursery. His subscription online learning site and library, Bonsai U, would be up and running by the start of 2020. In September 2023 Bjorn would confirm rumors that the following year he and Nanxi would be moving to Kyoto in late Spring to establish an Eisei-en there which was planned to open a year later. A wide-ranging episode of the Bonsai Time Podcast recorded in March 2024 is an hour-and-twenty-minute-long "From America to Japan: A Bonsai Odyssey with Bjorn Bjorholm."] (Owens, Mitchell "Meet the Brad Pitt of Bonsai," Architectural Digest, Oct. 31, 2014; "Bjorn Bjorholm," Bonsai Empire; assorted historical posts on his Facebook page; first and second podcasts) 1988 - A Florida Keys-collected buttonwood (Conocarpus erectus) ended up at Mary Miller's Big 5 Nursery and had been seen by bonsai artist Ed Trout a week earlier. It "spoke" to Ed the minute he saw it. He knew that because, while he did not buy it when he first saw it on the bench, he thought about it for a whole week. Ed rushed down there to his friend and teacher's nursery the next weekend, and brought the tree home as a present to himself on this Saturday before his 42nd birthday that year. The tree was residing in a white plastic 5-gallon bucket with drainage holes added. The tree screamed Literati or Bunjin style from the moment he saw it. And with the first styling, the tree seemed to "show me the way." One of Ed's dearest friends and Mentor would be Chase Rosade. Ed and Chase would do the initial styling of the specimen together in Ed's garden. It would be the cornerstone of his collection, the first tree he would say good morning to with a cup of coffee, and the last tree Ed would say goodnight to. It would be the favorite of Ed's wife, Tina, also, and she would have him place it in the garden where she could always see it from her chair in the living room. It would be named Runner Up/Finalist to the Ben Oki International Design Award in 1994 (amateur bonsai's highest prize which was coordinated by Bonsai Clubs International from 1991 through 2006). The final styling would be done by Ed in 1994-95, although a few visiting Masters such as Ben Oki, Dan Barton, and John Naka would give him advice on it. John, in fact, would choose this tree at the 1996 BSF Convention to do a critique on it in one of his programs. It would be one of the most gratifying moments in Ed's bonsai journey: to have the Godfather of American Bonsai talk very favorably about one of his trees would be an incredible experience. John would pick it as Best in Show. In addition, with Ed's talent and hard work the specimen would be chosen as the logo for that Bonsai Societies of Florida Convention which would be held in Ft. Lauderdale on Labor Day Weekend. The graphic artist, Alan Kieffer, a Gold Coast Bonsai Society member, would painstakingly and perfectly draw the tree whose image would appear on all the promotional materials for that convention. A picture of the actual tree would grace the cover of Florida Bonsai magazine in August of 1996, and in 1997 it would be selected as the logo tree for Gold Coast Bonsai Society (as per the February issue that year of Florida Bonsai). Ed would serve 3 separate terms as President of Gold Coast and be made a Lifetime Member. As the years passed, some of the other awards this tree would receive included: Chase Rosade Design Award 1996; Top 100 JAL World Bonsai Contest 1999; and the World Bonsai Contest Top 100 2006. In April of 2008, after some twenty years, the tree would be stolen from Ed's yard and never seen again. The specimen would have become Ed's teacher, and almost a member of his family would be what was stolen from their garden -- not "just a tree." Now all we have left are the pictures and the lovely logo of the Gold Coast Bonsai Society.]

(Facebook post by Ed Trout, Jan. 19, 2023; Ed's FB Messenger replies to RJB questions, 1/21/23, including year for purchase and year for BOID award corrected from original story; "Buttonwood Bonsai and a tragic story: A Special Buttonwood Bonsai" by Ed Trout, Bonsai Mary, earliest discovered save, Aug. 9, 2014; ) SEE ALSO: Jan 26, Jan 30, Apr 26, Jul 14, Aug 24, Sep 1 1998 -- After a year in quarantine, seven magnificent bonsai masterpieces from Japan were unveiled at a gala ceremony in the U.S. National Arboretum's National Bonsai and Penjing Museum. Funds for the donation were underwritten by the Nippon Bonsai Association (Japan) and the National Bonsai Foundation (U.S.). The oldest of the seven was a 250 year-old needle juniper (Juniperus rigida) in training for thirty years and donated by the Governor of the Saitama Prefecture. Two days following this ceremony two other additions were made to the Museum: a beautiful California live oak bonsai and a self-portrait, both created by John Naka. The painting was done at the request of the NBF and the Arboretum so that it could be hung in the museum as a lasting reminder of John's many, many contributions to bonsai. ("Arbor Friends," newsletter of the Friends of the National Arboretum, Summer 1998, pg. 1)

2000 -- William "Bill" E. Southworth died. (Born on April

30, 1924 in Fulton, NY, he had read of the collection of Ming trees at

the Brooklyn Botanic Garden in a 1939 [sic] issue of Life

magazine. When he was stationed as a Marine in China and later in Japan in 1946

he was first exposed to bonsai. After retiring from engineering

(after retiring from the Marines), he finally began studying bonsai

under Dick Whidman, John Naka, Harry Hirao, and Ernie Kuo.

Eventually he taught at Cypress College and later began teaching from

home. He helped the Vietnamese community form their own bonsai

club. He loved organizing bonsai exhibits and shows for the

various clubs and organizations and had many a tale to tell of the

successes and pitfalls of each one. Equally as interesting were

his recollections of his years spent in the maze of politics in the

bonsai community. Bill was a most ardent supporter of anyone who

wanted to try his/her hand and luck at training and raising these

beautiful, and at times exasperating, miniature living art forms.)

("In Memory of William 'Bill' E. Southworth,"

http://www.prepgraphics.com/kofu/Sale10/southworth.html,

accessed July 6, 2001)

|

||||||||

| 24 |

|

||||||||

| 25 |

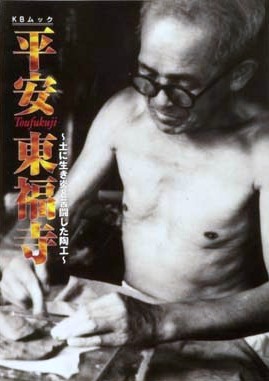

1890 -- Heian Tofukuji was born. [Originally he would be a comb maker.

When his job was eliminated fairly late in life, Tofukuji would decide to become a professional bonsai potter.

He'd live in Kyoto and use an oven in a local temple or the kilns of friends and fellow potters at first to fire

his pots. It would be difficult using a common kiln, often getting the bad position of having pots at the

outer circumference of the fire. However, Tofukuji would research and correspond with other potters about

this unfavorable condition, and from this would come consistantly excellent vessel forms, foundation soils, and

colors of glazes. He would be renowned for his beautiful handmade bonsai pots in different sizes and the

special glazings he'd use for them. He would become one of Japan's most respected potters. In his

long career as a potter Tofukuji would use more than twenty different rakkans (the maker's signature)

and it would therefore not always be easy to distinguish between a genuine Tofukuji pot and an imitation.

Several books would be published about his work. His son would also be a potter. The senior would

die in 1970. As with many artists, his works would begin to attract attention after his death and

subsequently prices for them would begin to soar. As using a common kiln would have necessitated the

firing of smaller pots, only decades after his death these containers would become valuable when shohin

bonsai overtook larger-sized bonsai in popularity.]

(van der Hoeven, Maarten "Special pots from Japan," Bonsai Focus, 4/2008, July/August, #116, pg. 84; "Heian Tofukuji," Sam & KJ's Suiseki Blog, 30 Aug. 2009, http://samedge.wordpress.com/2009/08/30/heian-tofukuji-%E5%B9%B3%E5%AE%89%E6%9D%B1%E7%A6%8F%E5%AF%BA/; "Glazed Pots by Heian Tofukuji," Japanese Bonsai Pots Blog, May 19, 2011, http://japanesebonsaipots.net/2011/05/19/glazed-pots-by-heian-tofukuji/; "Two Special Tofukuji Pots In Depth," Japanese Bonsai Pots Blog, January 13, 2012, http://japanesebonsaipots.net/2012/01/13/two-special-tofukuji-pots-in-depth/; "Heian-Tokufuji," http://www.yoshoen.com/tuhan/pot/pot_a12.html; a number of Tofukuji's creations are shown in the second, third, and fourth of these resources and also here and here) SEE ALSO: May 20 1967 -- Michael Hagedorn was born. [He would grow up in the mixed forest of Upstate NY. He would then develop an art background ranging from painting and drawing to ceramic sculpture and installation, with a Masters in Ceramics from the New York State College of Ceramics. He would make bonsai containers for nine years in the 1990's in upstate New York and Arizona, sometimes giving talks about what was involved from the clay particles to the kiln-fired pieces. But before all that, he would already be into bonsai; the Sunset book would trigger a passion for bonsai when he was only sixteen. After a second meeting with Boon Manakitivivpart at the 2000 Golden State Convention in Oakland, CA, Michael would study at a "bonsai intensive" hosted by this teacher. Too frequently in those last few years Michael would walk home after making pots in the studio and realize that he'd been thinking about trees all day. He would pack up this incomplete career, squirrel it away in a five-by-ten storage unit, and, at age 36 in December 2003, surrender to a rare opportunity. He would would travel to Obuse, Nagano Prefecture, Japan where he would apprentice for three years under bonsai master Shinji Suzuki. (Boon and Hideo Metaxas would have aided Michael during his introduction to Suzuki.) "The ranks of bonsai apprentices are dwindling, as easier careers proliferate. Mr. Suzuki would remind us to the point of sounding like a broken record that to be a deshi, or apprentice, was to become stronger and grow through our kurou, our struggle, and not to flinch from it. The two words were nearly synonymous: apprentice/struggle. Since apprentices are usually young and mostly lack kurou, it follows that they are in definite need of it. 'You cannot create great bonsai if you don't understand this!' Mr. Suzuki would repeatedly explain... Most enter apprenticeships as teenagers just out of high school and their master's job is not only to teach them a trade, but also to finish raising them. "New apprentices might arrive eagerly with tools in hand, with the natural assumption that their primary purpose is to study bonsai. They soon learn that this is a counterproductive concept to be burdened with. To masters, apprentices are commodities, and learning the art of bonsai - while important - is secondary. Apprentices enable the livelihood and success of their masters. The art of bonsai is transmitted along the way. Direct teaching is new in bonsai; particularly in past generations, very little formal teaching was done. Some of the younger masters have shouldered the new expectations and sometimes offer explanations for why we do what we do alongside the traditional structure of show and copy. Basic apprenticeship assumptions, however, have remained the same for a long time: the master provides room and board and work for the apprentice, and the apprentice does what the master says to do and commits to a certain term of stay. The agreement that [Michael] had with Mr. Suzuki was verbal. "Soji, cleaning, is a word a foreign apprentice will learn on the first day. For the most part cleaning is one of the few things an apprentice can do without being overly lectured, and so for those who clean enthusiastically there is some peace to be had. Each morning we swept up fallen leaves under bonsai benches, removed errant soil on top of them, pulled weeds, and scrubbed the studio - this took perhaps an hour if we were focused. We had three large greenhouses, a studio, and a museum across the street to clean. "Spring through fall, when plants are growing and dropping things, was our busiest time for keeping things tidy... More than once I found myself in muted rages against the fact of entropy itself. I later learned this was miles from the approved apprentice attitude. Attitude is everything. Mr. Suzuki strictly emphasized the tidiness and cleanliness of all areas. He instructs us, 'These carpeted paths are here for a reason - without them, clients will get mud on their expensive shoes. They get it in their car. They won't be back.' He looks at our blank, unenthusiastic faces and grins, saying, 'When I was a first year apprentice, all I DID was clean! You are lucky, working on trees in your first year.' "It is said that it takes three years to learn to water bonsai properly. I've heard masters admit in rare, transparent moments that they are still learning the finer points of watering. Many masters do not let incoming apprentices water the bonsai because it is such an important and complex job - more experienced apprentices will usually carefully monitor the watering and fertilizing. Watering and fertilizing is work done exclusively by apprentices, as masters are too busy with clients or other work. "The apprentice learns the tradition of bonsai by default. It was not fancy. We opened no books. I began by cleaning the studio, pulling weeds, and making tea; even lifting trees was initially off limits. I watched. I learned bonsai, and everything tangential to it, literally from the broomstick up. Very soon I was lifting trees, progressively larger ones until I was not much interested in lifting any more. I was allowed to water bonsai, fertilize them, spray for insects, repot, and wire them. Early on Mr. Suzuki might demonstrate on the branch of a bonsai what he wanted me to do with it. After several months I was styling bonsai while he was away for a week. Initially it seemed an odd and partial education. The abbreviated formal teaching we received was infrequent at best. We watched, and copied, and as a byproduct of this mute exercise, learned. Occasionally we might pick up some finer points from an obscure comment, as if it were a head-scratcher from a book of counter-intuitive sayings of Lao Tsu. Often the comments remained obscure, something to puzzle over when taking a tea break. Contemplated while rubbing sore biceps. At face value, this sort of teaching appears ridiculous. But eventually the fruits ripen. We were not taught equations, but how we ourselves relate to the questions. If everything is handed out and explained, little is actually learned, or at least understood in a gut sense. Passively acquired information rarely becomes primary and a guide for us. It's the stuff that we puzzle over and awaken to that remains as a touchstone. It becomes applicable. "Unlike the European guild system, the bonsai community in Japan does not have a controlling body. In the study of bonsai in modern Japan the standards are decided by the apprentice's master, not a syndicate of masters. When the term of study is completed, and the bonsai master is satisfied with an apprentice's level of skill, the apprentice is allowed to go to the Nippon Bonsai Association in Tokyo to receive a certificate entitling the new graduate to teach bonsai. There are no tests or masterpieces that need to be offered for review at the Nippon Bonsai Association. It is sort of an honor system that assumes masters will use their best judgment in sending students to pick up a certificate. It is rare in the bonsai community for an apprentice, after completing studies with one master, to then go and study at other places with other masters. The techniques from a bonsai studio are often seen as proprietary knowledge, not to be shared with others. Specialists have developed in bonsai - a master is known for his work on pine trees, for instance, or for deciduous work. They are covetous of their knowledge, and apprentices are often asked to keep secrets. With other apprenticeships this is not the norm. Zen monks, for example, often end their studies as peripatetic journeymen of sorts, moving on to study with other Zen masters. Depending on where the bonsai apprentice trains, the skills learned will be different. The profit margin in the business of bonsai is greater for those who are merchants - buying a bonsai from a client, auction, or estate sale at a low price and selling it for a higher price to another client - than for those who actively create bonsai. In a merchant enterprise, business and social skills are more critical to success than knowledge of bonsai technique. To rework a tree, and perhaps take a few years doing so in order to improve its aesthetics and value, is to be content with a slow financial turnover. Therefore masters often have specialties in this regard too, being either creators or bonsai or sellers of them, and incoming apprentices are often aware of this and may choose to study under a master who has better connections, or who is known to be an especially good artist, according to their interests. Many masters need to do both selling and creating. "[There was a] vast disparity of skills and quality [apprentices see around themselves]. It was apparent that only a few handfuls of masters actually understand the work of creating bonsai, and the rest either farmed their clients' trees out to these skilled masters to rework, or simply bought and sold them without trying to improve them at all. We could not help wondering about the future of bonsai in Japan... Times have changed in the Japanese bonsai world. Currently there is a dramatic falling-off of the numbers of apprentices entering into bonsai. Old photos from fifty years ago show as many as eight young apprentices at a time clustered around their master. The average now is one or two." Seven trees that Michael wired would be accepted into the Kokufu Show in Tokyo 2004, 2005, and 2006, two in the Taikan Ten, and one in the Sakufu Ten. Michael would also be honored by Suzuki-san to do the wiring on two trees that went on to win a Kokufu Prize and Prime Minister Award. On Michael's return from Japan in 2006 he would settle in Portland as a professional bonsai artist, where he'd create, teach, and write about bonsai. Shortly after returning he'd set up the Seasonal program for those willing to travel to study bonsai in Portland. In 2008 he would author an anecdotal book of his apprenticeship, Post-Dated: The Schooling of an Irreverent Bonsai Monk. He would have a couple more books in the works, and would blog weekly (from his long-standing website http://crataegus.com/, which would date from at least January 1998). Michael would be a founding member with Ryan Neil of the Portland Bonsai Village. Michael's efforts there would be focused on promoting excellence, forming a viable professional network and showcase, and inspiring bonsai enthusiasts nationally and internationally. A two-part interview with him would be published in Stone Lantern's blog, Bonsaibark, in early 2009. (See also these still photos and video of his garden here.) He would be involved with Neil Ryan in presenting the Artisan's Cup in September 2015 in Portland, OR. In December 2015, as part of Bonsai Empire's 15-year anniversary celebration, Michael would be one of several international artists and teachers chosen to answer reader-submitted questions. Michael's topic would be "What we learned about Bonsai since John Naka." In May 2020 his second book was published, Bonsai Heresy, 56 Myths Exposed Using Science & Tradition. An episode of the Bonsai Time Podcast from early March 2023 is an almost two hour-long "Insights into the Bonsai Art of Michael Hagedorn."] ("Bio," Crataegus Bonsai, http://crataegus.com/bio/; Post-Dated, pp. 14-15, 22, quotes from 38-40, 45-46, 53, 175-176, 179-182, and 186-189, 216; "Michael Hagedorn Biography," http://bonsai-bsf.com/?page_id=774) SEE ALSO: MarAlso, Sep 25, Nov 21 1977 -- Mas Kurosumi died of a heart attack at age 53. (Mas was the first importer of bonsai pots into the U.S. to try to understand the needs and tastes of bonsai growers. Other importers had been bringing in the same type of pots for twenty years and were not about to change. Mas would listen to what the retailers were saying and, as a result, the bonsai watering nozzle came into existence. He was a salesman for the Toyo Trading Co. for more than ten years before going into business with another salesman. But having suffered his second heart attack in five years, he dissolved the partnership because of his health. In 1972, however, Mas restarted in the import business on his own under the name of Sanyo Imports. It was at the 1974 joint BCI/ABS Convention in Pasadena, CA that he first attracted attention with his variety of different containers. Appearing at both the BCI Conventions in Miami Beach (1975) and Washington, D.C. (1976), his contacts and friends in the world multiplied.) (Komai, Khan "In Memoriam," Bonsai Magazine, BCI, Vol. XVI, No. 6, July/August 1977, pg. 162.) 1995 -- Arch Hawkins, editor of the American Bonsai Society's Bonsai Journal since the summer of 1992, died. (A founding member of the bonsai clubs in Dallas (1965), Austin (1966 but short-lived; reborn in 1972), and Houston (1971), he was named an outstanding bonsai artist by the National Bonsai Foundation in 1987. He was a member of both ABS and Bonsai Clubs International and wrote articles for both organizations' publications.)

2010 -- Author and teacher Jerry Stowell died about a month and a half shy of his 83rd birthday at Hunterdon Care Center, Raritown Township, NJ. ("Jerry Stowell," posting by bonsaistud, 2 May 2010, http://ibonsaiclub.forumotion.com/announcements-f5/jerry-stowell-t2925.htm) SEE ALSO: Jun 9 2017 -- Cheryl Owens, 90, passed away in her Elkhart, Indiana home, after an extended illness. (A graduate of Elkhart High School, Cheryl worked as a secretary at Ames Company/Miles Laboratories, where she met her husband-to-be, Charles V. Owens, Jr. (Cheryl was a master gardener and created a beautiful oasis around her home on the St. Joseph River. It was often featured on garden tours. She was perhaps best known as a bonsai enthusiast, having studied with Japanese masters of the art, and was thrilled to be one of the few outsiders given the privilege of visiting the Imperial Bonsai Collection in Tokyo, Japan. In addition to her studies with John Naka, Cheryl made a number of trips to Japan, Korea and Taiwan to study bonsai. She generously shared her knowledge of bonsai in schools and with the various bonsai and garden clubs of which she was a leader and member. From 1968 until 1978 the "Elkhart Bonsai Club" and from 1988 until 2008 the "Elkhart Bonsai Study" group met once a month in the Owens' bonsai garden. In 1972 the Elkhart club had its first exhibit and demonstrations at the Pierre Moran Mall. The Michiana Bonsai Study group is the latest in a succession of bonsai clubs in the South Bend-Elkhart, Indiana area, coming into being by a vote in the fall of 2010 of the members of the Wellfield Bonsai Study group. Cheryl was an American Bonsai Society (ABS) director from 1976-77. She authored two articles in 1977 for the ABS Journal. She was the author of six articles in the Bonsai Clubs International (BCI) magazine between 1972 and 1999, and a vice-president of BCI in the mid-70s. Cheryl and Charles were the 2001 winners of the BCI Meritorious Service Award. The pair then honored Ben Oki, John Naka's premier student and a master in his own right, with both the Ben Oki International Design Award and the Ben Oki National Design Award -- the awards for excellence in bonsai design quality sponsored by the BCI and the (ABS), respectively. (Cheryl was also a member of the Embroiderers' Guild of America and accomplished at embroidery, needlepoint, knitting and other needle arts. She also had a strong interest in Native American art and culture. Fiercely independent and opinionated, Cheryl was often teased by her children for the vast accumulation of random trivia that she picked up, and always shared. She was a gracious host, curious about the world and a friend to many across the globe. Throughout their life together Cheryl and Charlie traveled extensively, visiting every continent except Antarctica. He predeceased her in June 2008, after 50 years of marriage.) [Cheryl is survived by her sister, five children, eight grandchildren, and 2 great grandchildren. Memorials may be given to Frederik Meijer Gardens & Sculpture Park, Grand Rapids, Michigan (about 90 miles to the north of Elkhart) for care of the Owens' bonsai collection.] (Personal email to RJB from Cat Nelson, 04/26/2017; "Cheryl Owens," South Bend Tribune, April 28, 2017, http://www.legacy.com/obituaries/southbendtribune/obituary.aspx?n=cheryl-owens&pid=185230698&fhid=8850; "About Us," Michiana Bonsai Club, http://michianabonsai.club/; "Ben Oki," Bonsai Society of Florida, http://bonsai-bsf.com/?page_id=795; The Indices for ABS and BCI, 2004) SEE ALSO: Mar 16 |

||||||||

| 26 |

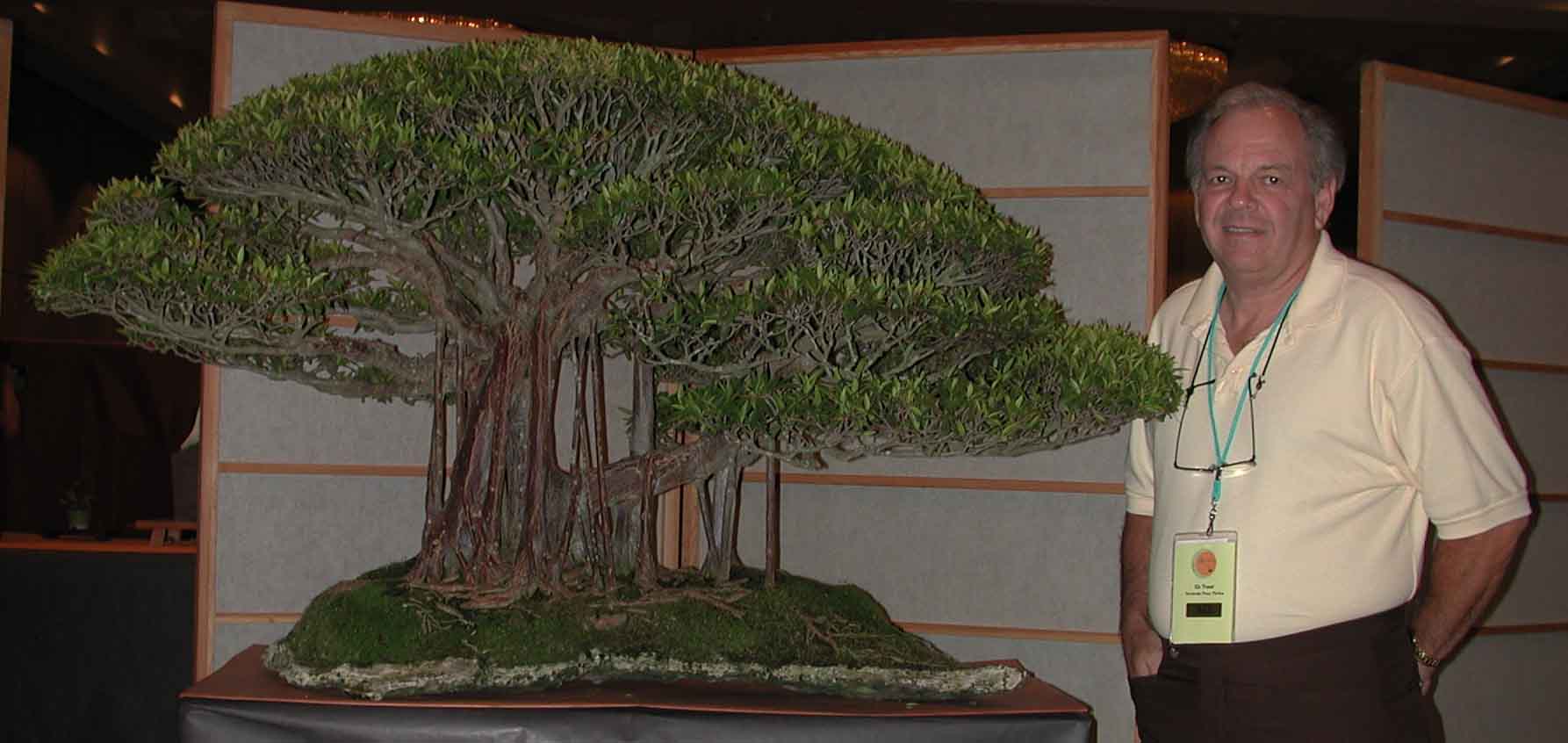

1946 -- Ed Trout was born in Akron, Ohio. [At the age of three, his father and

mother would move with him to Miami, FL. His father, a food store manager, would be transferred to Key West

three years later. This would become Ed's hometown and he would graduate from Key West High School in

1964. Later Ed would write, "On October 01, 1971,

Walt Disney World opened.... and [at that time] I

began my bonsai journey, after buying my first tree [and a couple of books at the Sarasota Bonsai Gardens] on our

way home from that opening! And as an exhibitor in Walt Disney's EPCOT Flower & Garden Festival since its

beginning over 24 years ago, Walt Disney has been a big factor in my love of Bonsai!! Thank you Walt!!!" [Now, that first tree would have been an imported Japanese white pine (Pinus parviflora), which species would not thrive in Florida. It would soon die and Ed would be determined to find out why. (Ed's grandfather would have grown up on a farm and always have vegetables and fruit trees in his yard in Miami. Ed would feel he inherited his interest in plants from him.) Ed would then attend the very first Bonsai Societies of Florida convention on Miami Beach in 1975. When he saw the plant material being used by those early pioneers, he would realize that he'd need to grow trees native to his environment. One of those early pioneers would be Joe Samuels. Ed would study his work, find out that he kept his collection at a local nursery and would begin making regular Sunday morning trips to the nursery to just watch Joe work. When John Naka and then Ben Oki would begin making regular teaching trips to Florida, they would become very influential to Ed also. Ed would admit that he partly got into bonsai because he had a stressful job at Warren Technology in Hialeah, FL and would need some type of a hobby to relax him. "Bonsai is one of those hobbies [in which] you can lose yourself. I'm not sure if I believe in the Zen description that everybody explains, but I do know it happens; you get out here in the garden for a couple of hours and you just lose yourself in the world and everything goes away..." [Mary Madison, the "Queen of Buttonwoods," would be his principle teacher after Samuels. Ed would become a President and a Lifetime Member of The Gold Coast Bonsai Society, one of the first clubs (est. 1967) in Florida, and would be an Honorary Member of several other Florida and Texas bonsai clubs. He would also be a President and Lifetime Member of The Bonsai Societies of Florida (est. 1973), a Board Member of The American Bonsai Society, a Board Member of The National Bonsai Foundation at the US National Arboretum, and a Board Member of Bonsai Clubs International (1996 through 2003). Ed would contribute many articles to several different publications over the years, including World Tropical Bonsai Forum (1990), Bonsai Today (1990 and 2001), Bonsai Focus, at least 8 articles in BCI's Bonsai Magazine (1992-2000), and photographs of some of his trees would be used in the 1994 edition of the book Sunset Bonsai. Ed would appear on several local television programs and be asked to do a bonsai program for PBS-TV, "At Gardens Gate," filmed at Cypress Gardens in 1999. He would be featured in several local newspaper articles. He would author a booklet titled "Bonsai, Before and After" for the American Bonsai Society in 2006. He would exhibit his trees at many conventions, including the 1993 World Bonsai Convention in Orlando, FL and the one in 2005 in Washington, DC, and also the 2012 and 2014 U.S. National Bonsai Exhibition in Rochester, NY. Ed would be invited to display trees every year in The Japanese Pavilion at EPCOT in Orlando, Florida, since 1994. He would be honored to be a finalist in the 1994 Ben Oki Award, and to have trees selected in the Top 100 of The World Bonsai Contest in 1999, 2001, 2002, 2005, and 2006. He would be U.S. South East Regional Director of the North America Bonsai Federation. Although he'd specialize in tropical bonsai material like lantana, ficus (especially F. nerifolia/salicifolia), buttonwood, Bucida, and bougainvillea, his private collection would also include pines, junipers, and several deciduous species that all do well in his Zone 10C environment. Ed and his wife Tina would always be very active in their local clubs, Ed presenting many workshops and lecture-demonstrations. [Tina, wife of 37 years and mother of their son and 2 daughters, would pass away near the end of May 2015, and Ed would be able to share his several year grief journey with the compassionate bonsai community on Facebook, which Ed would have joined in 2009. (By her own wishes, Tina's ashes would be in a memorial garden at their Miami home so she'd always be with him. Another challenge faced would be that their granddaughter, Chelsey, would pass away in 2012 because of leukemia.) [In early August 2018 Ed would post the following on his Facebook page: "This year marks my 46th Year practicing the wonderful art of bonsai. Hundreds and hundreds of trees worked on all over the US, Canada, and the Caribbean. Thousands of feet of wire applied, hundreds of gallons of soils used. Many, many smiling faces... happy to be starting their journey in bonsai. My life has been made important to me thru the time spent in my own garden, creating my own trees, and nurturing their progress and existence. And my life has been made better thru the endless number of friends made thru bonsai, all over this world. But all things good come to an end. My health no longer allows me to fully enjoy workshops, demos, or even working in my own garden. I've been at this crossroad before, and fought thru it. But the time has come. During the next few months, I will slowly be selling off what few trees remain in my garden. My first priority (other than my family) has always been to The Trees. They do not deserve the absence of care that comes with an aging caretaker. An end zone all of us will reach someday. What a Journey this has been! ...And I've got some of the best friends in my life through the art of bonsai, some I've never met. That's what I'm very thankful for." [When renowned bonsai potter Dale Cochoy would die on Dec. 31, 2018, Ed would post the following on Facebook: "Lost a good friend yesterday [sic]. An artist, an innovator, a generous Soul, and a fellow Akron, Ohio resident. I took my Mom to a bonsai convention many years ago... introduced her to Dale Cochoy because I knew we were raised in the same city... and then astonishly discovered that my Mom was raised in Akron, on the same street as Dale's parents... Two doors down!! The world is small. And tonight, the world is sad. Rest In Peace my Friend.... And Your Beautiful Work Lives On!" [Per an April 2019 FB message to RJB, "In spite of my health issues, I have decided to maintain a small collection (15-20 trees) in my garden, way less than the 150-200 trees I once had. I believe it is not the number of trees you have, but it is the quality time you spend in your garden that makes the art of bonsai so special. I am committed to fulfill my bonsai program schedule for at least this year, which are limited to sessions within driving distance from home, working with clubs and study groups." [At a club bring-your-own-tree workshop in 2019, Ed would meet student Betty Cruz Siskind. They would be married on February 25, 2022. "Once again The Art of Bonsai has enriched my life, made me a better person, and made it possible for me to meet this incredibly beautiful and talented woman, who I love very much! I'm having The Time of My Life!!!," Ed would relate on May 8, 2022. Betty would have gotten into bonsai because she loves plants and gardening. She would work as an assistant at The Bonsai Supply in Ft. Lauderdale, where Ed would also consult. She would have been doing bonsai since about 2010, and her specialty would be flowering trees. [Per an October 7, 2023 FB post, "I've practiced the Art of Bonsai for more than 50 years now. I have learned that the best moments we have in this wonderful hobby is the one on one Journey we take with each of our trees. And when we can pose those trees in a display, it's an even better feeling. Display your trees for your own pleasure….that's what they're for !!!"]

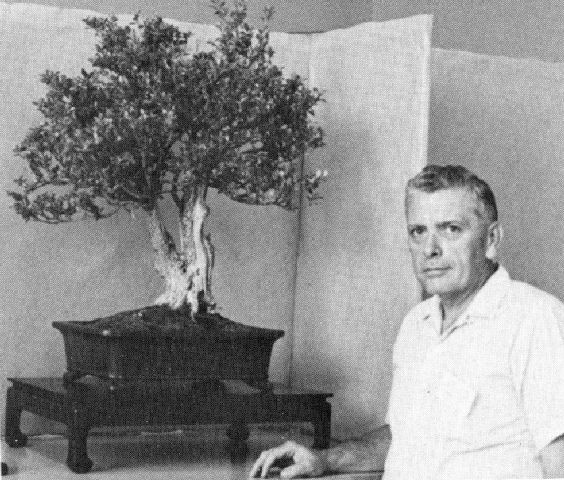

Ed Trout, 07/05/02.

(Photo courtesy of Alan Walker, 05/11/07)

("Our Teachers," American Bonsai Society; Schmitz, Dorothy "Profile: Ed Trout," The Art of Bonsai Project, December 22, 2006; "The Bonsai of Ed Trout," The Art of Bonsai Project, with color photos of 11 of his trees; "Ed Trout's Interview and Bonsai Garden Tour" YouTube video; Facebook posting on August 5 and October 2, 2018, May 26 and May 30, 2019, ; FB message to RJB April 13, 2019 after reviewing a draft of this listing, plus two lower photos; The Indices of Bonsai Magazines, 2004; Facebook posting on May 8, 2022, with additional comments and photo via Messenger to RJB after being asked for expansion on those thoughts.) SEE ALSO: Jan 26, Apr 9, Apr 23, Apr 29, May 9, Dec 31 |

||||||||

| 27 | 2001 -- The final 6 winning pots of the First North American Bonsai Pot Competition were announced on this day at the opening of the Asian Arts Festival celebrating the 25th Anniversary of the National Bonsai & Penjing Museum. Sponsored by the National Bonsai Foundation in association with the Takagi Bonsai Museum of Tokyo, the competition had two categories: modern and traditional. Jim Barrett took first prize in the former and Sara Rayner in the latter. [Their wares, along with those of the second and third prize winners in both categories, would be on display at the Museum through July 29.] ("Winners of the First North American Bonsai Pot Competition, http://web.archive.org/web/20040218005323/http://www.bonsai-nbf.org/nbf/potcomp2001/potterywinners.htm.) SEE ALSO: Jan 4, Mar 28. | ||||||||

| 28 |

1905 -- Heian Kouzan was born into a long line of

Seto potters going back more than 12 generations.

[By 1918, at the age of 13, he would already be making

an income with bonsai and pottery. Pre-Pacific war pots would use a white clay, while post-war pots would

use reddish clays. This would make white clay Kouzan more valuable and rare, as they would have been made

before he became famous and are early works. By 1948, at the age of 33, he would be famous for the

austerity and simplicity in his design of shohin pots and his special colors. Kouzan's work would

be known for relatively thin-walled and delicate construction, despite which his pots would be mathematically

precise, with strong straight lines and corners. For this, he would earn the nickname "The Razor."

He would use molds in his earlier pieces, but apparently would not in his late work. Similarly, his early

work would be created in the climbing kiln before Kouzan

would begin using gas or electric. Kouzan would perhaps be best known for glazed pots, his most famous

being blues, chicken blood reds, and greens. However, his work would be very diverse, and include carved

decoration and window motifs as well as painted pieces. Pots made by Kouzan would be too valuable to be

subjected to weather conditions and such pots would often only be used during exhibitions. This would be

common in Japan. When the pot was not in use it would be stored in a cupboard or in a special cloth

wrapping, sometimes made of silk. In 1973, handing the family pottery name off to his son, Kouzan would

change his trade name to "KouOu" or "Old Man Kou." Some of his best work would come from the 1973-1990

"KouOu" period, especially unglazed pieces, as this would be the era when shohin bonsai took root, along

with "deadwood style" conifers. Heian Kouzan Sr. would pass away in 1990. The 143 page book

Charisma, Yusen & Kouzan would be published in 2006 about the potters Tsukinowa Yusen and Heian

Kouzan.]

"Heian Kouzan (KouOu) Jr and Sr at the second Gafu Ten exhibition in 1978 where a special display was presented of

Kouzan pots."

("Heian

Kouzan, Part 1," Japanesebonsaipots.net, April 14, 2013, with many color photos of the pots, and

Part II

with many photos of mostly unglazed pots; van der Hoeven, Maarten "Special pots from Japan,"

Bonsai Focus, 4/2008, July/August, #116, pg. 85; Edge, Sam,

"Bonsai Pot Books to Own, Sam &

KJ's Suiseki Blog, Sep 7, 2009)

(Photo from japanesebonsaipots.net article, "Heian Kouzan, Part 1") |

||||||||

| 29 |

1994 -- Beginning today and running through June 5th, the Bonsai Societies

of Florida's First Exhibit of Bonsai occurred at the Walt Disney World's

EPCOT

(Experimental Prototype Community of Tomorrow) near Orlando, Florida.

The bonsai exhibit coincided with the six week Flower and Garden Festival.

(That Spring, a meeting at the WDW Horticulture office to plan for the

first annual Festival was attended by Mrs. Mary Jane McSwain, the Garden

Editor for the Daytona Beach News-Journal newspaper. She contacted

BSF president Tom Zane and proposed that the BSF arrange for the loan of

bonsai. Tom called a planning meeting at Jim Smith's nursery in Vero

Beach. A partnership contract was negotiated between BSF and WDW

for the loan of 16 large (30 inches or taller) show-quality bonsai.

Frank Harris of the Central Florida Bonsai Club acted as the liaison between

BSF and WDW to coordinate the setting up and monitoring of the annual exhibit

(a post he has continued to serve.)

[This cooperative venture would take place every year since. Annually, a request would go out to the BSF membership to submit photographs of bonsai which they would like to have considered for inclusion in the exhibit. BSF and WDW would then make the final selection. The trees and their owners generally would arrive at WDW the day before the exhibit is to be mounted. Along with a highly professional staff of gardeners and laborers, they would meet at the Japan pavilion and place each tree securely on its display stand. Bonsai are displayed at the torii along the shore of the World Showcase Lagoon and at the "Meadow" behind the Pagoda, as well as on the porch of one of the restaurants. During the Flower and Garden Festival the WDW staff would water the trees twice a day and perform periodic inspections to insure that no tree is in stress or is being attacked by insects or fungus. Several times a week one or more members of the Central Florida Bonsai Club would also check on the condition of the bonsai. The result is a win-win situation for everyone, including all of those park visitors.] ("BSF Exhibit of Bonsai at EPCOT" by Thomas L. Zane, http://www.bonsai-bsf.com/epcot_process.htm ; personal e-mail from Tom Zane to RJB, May 30, 2002) SEE ALSO: Sep 9, Sep 15 |

||||||||

| 30 | 1998 -- Asteroid 1998 HE43 was discovered by the Spacewatch Project at Kitt Peak Observatory, Arizona. This minor planet, the 12515th one identified, would be given the name "Suiseki" (lit. "water stone"). (Schmadel, Lutz D. Dictionary of Minor Planet Names (Springer, 2003, fifth edition), pg. 784.) SEE ALSO: Dec 14 |