SABURŌ KATŌ

International Bridge-Builder, His Heritage and Legacy, Part I

+ ![]()

Compiled by Robert J. Baran

This Page Last Updated: November 21, 2024

International Bridge-Builder, His Heritage and Legacy, Part I

+ ![]()

Compiled by Robert J. Baran

This Page Last Updated: November 21, 2024

|

Jihei Katō had been in the horticultural business in mid-19th

century Japan. His son, Tomekichi, established the Mansei-en nursery in Tokyo. At that nursery

could be gotten orchids, evergreens and foliage plants. Tomekichi traveled extensively throughout

Japan and became recognized for his knowledge of plants. After his business had become well established,

he began to also develop an interest in bonsai. As he and his wife produced only five daughters and no

sons, the family name could not continue unless a man was willing to marry into the family and assume the

family name of his wife -- a relatively common practice in Japan. It was also a common practice for an

apprentice to assume the name of his mentor upon the latter's passing.

Enter a young man who had been born on January 4, 1883 into the Taketa family. As a young man he had developed a keen interest in horticulture and bonsai. He wanted to study under the guidance of Tomekichi Katō, but Katō-san did not want to have any students. Taketa persisted and eventually was allowed to work and learn at Mansei-en. After two years of basic cleaning work he was allowed to care for the bonsai trees. Learning the techniques of grafting and wiring, he began to creatively develop nice bonsai -- which he sold to Tomekichi. Taketa was eventually allowed to marry the nurseryman's oldest daughter, and he thus assumed the Katō family name. (It was either when his father-in-law died that Taketa assumed the name of Tomekichi Katō II or at the time he assumed responsibility of the now exclusively-bonsai Mansei-en). Now, he was especially fond of shimpaku (Juniperus chinensis), goyo-matsu (Pinus parviflora, five-needle pine), tosho (Juniperus rigida, needle juniper), and ezo-matsu (Picea glehni Mast., aka Picea jezoensis, Ezo spruce). The latter had been lovingly cultivated by a certain group of bonsai artists since the late nineteenth century, but they were not fully recognized for their potential until around the time of the Great War when many trees from the north were being brought into Honshu, the main island of Japan. Tomekichi Katō (II), an outstanding master and second-generation proprietor of the Mansei-en Bonsai Garden, was the one first taken with the beauty of the Ezo spruce. He promptly brought them back from Hokkaido and popularized them.

Ezo spruce would not grow vigorously because of the impeded development of their roots and would continue to survive and grow a little because of some small fine roots growing in the upper part of the layer of sphagnum moss. Due to the long winters, the growing season was extremely short. Since the tree must open its buds, become active and achieve its entire growth in the four or five month humid period from the beginning of June to the end of September, it has dwarfed shapes suitable for bonsai. Collected and returned to Honshu in mid-September, the Ezo spruce would produce beautiful light green new growth the following spring. The trees were initially planted in sphagnum moss to duplicate what seemed to be the most important growing medium in nature. Because of the new growth, one would think they were fine and sell them. As time passed, however, the trees would lose their vigor and by the end of their third containered year, most died. Katō would return once or twice a year with 400 to 500 small Ezo spruce trees. Thousands of trees are said to have perished this way. It would be years before the masters of bonsai found ways to keep the tree strong and responsive to training. 1 Since the deaths of so many Ezo spruce had been taking a tremendous toll both financially and emotionally, Tomekichi Katō's colleagues suggested that he stop dealing in Ezo spruce. (Katō, in the meantime, was one of the founders of the new Bonsai Village on the edge of the town of Omiya. Following the Great Kanto Earthquake of 1923, Tomekichi allowed many of his neighbors whose homes were destroyed to live temporarily in Mansei-en. There were approximately 50 people living there at one time. The bonsai master -- who would attract many apprentices and be known as a great mentor -- and two friends began looking for an alternative site and found some land in the little village of Omiya, northwest of the capital. In 1925 the Katō family moved there. During the first few years, only three or four growers moved to Omiya, but by 1935 over twenty bonsai nurserymen and growers were located there.) Taken with the beauty of the trees, Tomekichi Katō experimented continuously to find a method of somehow fertilizing, watering or potting to prevent the trees from dying. One day around 1928, he took an Ezo spruce out of its container while transplanting. He noticed that after taking off the tattered roots there was rotten sphagnum moss in their midst. The material that remained looked like the sediment that remains after making tofu. After carefully removing this he planted the tree in a normal potting soil. The tree grew healthy. Although the trees grew naturally in the moss, Katō realized that using sphagnum moss was the problem. (Since the temperature in the natural growing environment was low, it took a long time for the sphagnum moss to decompose. During this time, the Ezo spruce roots could grow healthy. Conversely, using the sphagnum moss in a warm climate caused it to decompose faster than the roots of the trees could grow, and the roots would rot as well.) Tomekichi Katō's eldest son, Saburō (born on May 15, 1915), learned the fundamentals of bonsai from his father. Of the many teachings he received, the most memorable lessons was "to create good bonsai, you have first to build good character in yourself." Saburō learned well. And, despite his frail body, he accompanied the "father of ezo matsu" many times up to Kunashiri Island to collect these trees. 2 The bonsai growers of Omiya wanted to donate an Ezo spruce to the Imperial Household's bonsai collection. The task of preparing a suitable tree fell naturally to Tomekichi. After many hours of work to make it perfect for the great honor, the tree was donated in 1934. This was but the first of several trees from Omiya which were donated to that collection and, in the end, the Imperial Agency did actually purchase that Ezo spruce.

Tomekichi Katō died in 1946 at age 64, and his son Saburō assumed the responsibility of Mansei-en nursery. Extreme hardships were suffered by bonsai nurserymen in war-ravaged Japan when very few patrons could afford to buy bonsai. However, it was the American GI's of the Occupation Forces who came to Omiya to buy black pine and became interested in learning about bonsai that inspired the nurserymen there to persevere and continue their trade. Instead of paying money to Katō, the GI's brought food -- sugar, chocolate, meat and more. Katō was even more happy with those precious supplies than money since money was not as useful in those days. Meanwhile, an adjutant of Gen. MacArthur visited Katō one day and asked him to teach bonsai to the Americans at the bases. This he did for one year. Katō was so happy that bonsai became an object of interest for foreigners, and he was grateful that members of the American occupational forces also adopted the Japanese custom of purchasing potted pine, bamboo and flowering plum arrangements for New Year gifts. He acknowledged the help and kindness he received and to this day credits the successful revitalization of bonsai to post-war bonsai interest by Americans. This interest strengthened the faith of the few remaining growers and they resolved to continue and rebuild the culture. Subsequently, there was a rebirth of bonsai first in Omiya, and later throughout Japan." (Members of the Occupation Forces were the only people who could afford to purchase his bonsai and Katō would often credit these people with helping to save Mansei-en during the critical first few post-war years. It took 7 to 8 years until the Japanese rekindled their interest in bonsai after the war.) 3 Katō in 1963 had his first work published in Japanese, Yoseue: Ishizuki bonsai to Ezo Matsu (Ezo Spruce, and Forest and Stone-Clasping Bonsai). This relatively small 142-page illustrated volume provided the most comprehensive procedures for making bonsai with this species of tree. He still had several of his father's Ezo spruce bonsai in his prized rock garden at Mansei-en. On February 11, 1965 the thirty-one year old private Kokufu Bonsai Association was reorganized into a public corporation, under the auspices of the Japanese Ministry of Education, as the Nippon Bonsai Association. Saburō Katō was one of the founding members and Directors. By the mid-1970s the NBA had about 14,000 members and 132 local branch associations. 4 In 1967 Katō co-authored with Nobukichi Koide and Fusazō Takeyama, as the Directors of the Nippon Bonsai Association, The Masters' Book of Bonsai. (Koide, one of the major leaders in helping the bonsai community recover immediately after WWII, greatly influenced Katō as the latter matured as a bonsai artist and master in his own right.) Katō founded the Nippon Bonsai Kyodo-Kumiai (Japanese Bonsai Union, a professional bonsai growers association) in 1969 and became its first Chief Director. (Also this year, Keiko Yamane opened the Keijukai Bonsai School, specializing in grasses and accent plants. She had studied under Saburō Katō at Mansei-en in Omiya since 1964. She was the first woman to study and train in bonsai for a professional career, owning and operating her own nursery, winning many awards for her work.) 5 In 1970, the Osaka World Exposition was the first such exposition to take place in Asia. The theme of Expo '70 was "Progress and Harmony of Mankind." Its special features were the many exhibitions and film and slide presentations about space technology. Seventy-seven countries participated and fifty million visitors attended. From March 15 to September 13 and sponsored by the Japan Bonsai Society, Inc., the Japan Suiseki Society, and the Japan Satsuki Club, a large-scale bonsai and suiseki show was held in conjunction with Expo '70. The Japanese garden area alone covered sixty-four acres. Saburō Katō managed the bonsai exhibitions, which were continually changed. New replacements were brought in so that during the run approximately two thousand of the most famous and honored trees in the land would be displayed. The bonsai were impressively staged on benches outdoors, uncovered except for two corner areas with an overhead roof. Simple, but good-looking stands were made of smooth wood boards set on small uprights. Labels provided the Japanese name, botanical name, age, and owner of each bonsai. Nearly every bonsai there was in an old Chinese pot 200 to 300 years old. These pots are collectors' items and many are as well known and named as the trees they support. (Also this year, Saburō Katō's mother, Hana, died.) 6 In 1973, Kyūzō Murata edited Commemorative Bonsai Exhibit on the Occasion of the 27th Anniversary of the Death of Tomekichi Katō, a work in Japanese published by Saburō, Terukichi, and Hideo. This was a catalog of an exhibit held at Mansei-en, Omiya City, on September 20. Three years later, Saburō made the trip abroad to attend the U.S. Bicentennial as part of the Japanese delegation that made the presentation of 53 dwarf potted trees and six viewing stones from the Government of Japan to the National Bonsai Foundation at the U.S. National Arboretum. (This was only fitting as he had stepped in earlier and had persuaded the Japanese Ministry of Foreign Affairs that the U.S. could care for the bonsai. (Please see this documentary about the gifting, Bonsai Fly to U.S.A..) A tour group of 52 Hawaii bonsai enthusiasts visited Japan for two weeks at the start of November 1977. During their visit to Mansei-en they were given a lecture/demonstration by Saburō assisted by brother Hideo Katō on concepts of group planting, rock planting, pruning, wiring, and shaping. While his remarks were translated into English, the demonstrative graceful gestures of Katō Sensei and his highly visible love and kinship to the bonsai was readily assimilated by the largely English-speaking group even without the benefit of translation. Katō did not ordinarily teach bonsai through the conduct of regular classes. Later, during a courtesy call upon some of the directors of the Japanese Bonsai Association, members of the latter were invited by the Hawaii Bonsai Association to attend the IBC Convention to be held in Hawaii in 1980. Saburō Katō was invited to teach and demonstrate bonsai in Australia and New Zealand in 1978. (During this year and the next, The Masters' Book of Bonsai, now in its third edition, was translated into French, German, and Dutch.) 7 On April 19, 1980, the First World Bonsai Convention was held in Osaka during the World Bonsai and Suiseki Exhibition, which ran from April 16-May 6 at the Expo '70 Commemoration Park. Representatives from Japan, Argentina, England, West Germany, India, Italy, China, Korea, Spain, Canada, and the United States attended. The exhibition was the largest one ever staged, with over eight hundred trees and stones from Japan, and seventy-two photos of bonsai (due to quarantine regulations) from fifteen other countries shown on fifty photographic panels. Similar exhibitions have been held annually ever since. 8 At this particular convention, Saburō Katō convened a conference of bonsai leaders who unanimously adopted this resolution:

This year, too, Katō was appointed to permanent Director of the Nippon Bonsai Association., as well as consultant to the Japan Bonsai Union. In 1983 Katō was appointed to be the Executive Director of the Nippon Bonsai Association. He succeeded his mentor, Nobukichi Koide. The Masters' Book of Bonsai saw its first American paperback edition.

This year also saw K. Murata editing the book

Father of Ezo Spruce: Mr. Tomekichi Katō, 100th Anniversary of His Birth.

10

The formal inaugural meeting of the World Bonsai Friendship Federation (WBFF) was also held now. In planning since 1980 when it was tentatively called the International Bonsai Association, the WBFF was organized as an international non-profit organization to be governed by nine directors -- Saburō Katō was elected executive director -- representing nine world bonsai regional federations. Its purpose is to encourage a deep friendship and mutual understanding through the peaceful shared art of bonsai. (As the result of stress from the convention, Katō spent three days in the hospital -- for the first time in his life.) The Encyclopedia of Bonsai was published this year in Japanese. Shinji Ogasawara had written the article for it about Tomekichi Katō. 12 Ted Tsukiyama's article, "Profile of a Bonsai Internationalist: Saburo Kato," was published in the May/June 1990 issue of BCI's Bonsai Magazine. At the BCI convention from July 4-7 in Honolulu, Katō was the headliner with Shinji Ogasawara and John Naka. During the October 1 dedication ceremonies at the National Arboretum in Washington, D.C., Katō presented the deed of the John Y. Naka Pavillion and the deed of the National Collection of North American Bonsai to his longtime friend Naka. The Asia Pacific Bonsai Convention and Exhibition was held in Bali in June of 1991. Organized by the Indonesia Bonsai Society and supported by the Nippon Bonsai Association and the Japan Suiseki Association, the event's principal headliner was Saburō Katō. The 2nd World Bonsai Convention, "New Horizons," was held in Orlando, FL from May 27 to 31 1993 in conjunction with the BCI and ABS conventions. Katō, Naka and Yuji Yoshimura headlined for the seven hundred plus delegates who attended. In 1994 from October 21 to 23, the European Bonsai Association held its annual Congress on the southeast coast of Spain. Assisted by younger brother Hideo, Keiko Yamane, and four family friends from Omiya, Saburō Katō was the principle demonstrator before an auditorium crowd of up to 400 persons from Belgium, Colombia, England, France, Germany, Holland, Hungary, Italy, Japan, Korea, Luxembourg, Monaco, and the US. A tall, impressive forest of Scots pine ( Pinus sylvestrus ) from Spain on a very large slab using a soil-mix from Japan was the masterpiece created. Interpreters were available at all times for English, French, and Spanish translations. Katō enjoyed an established reputation as master of the bonsai group planting and the foremost expert on Ezo spruce bonsai. 13 The 3rd Asia-Pacific Bonsai and Suiseki Convention and Exhibition was held in Singapore between May 25 and 29, 1995. The theme was "Friendship Through Bonsai and Suiseki." Talks were given by Saburō Katō of Japan, Sze-Ern "Ernie" Kuo of the U.S., and a half dozen others, each from a different country. 14 On April 23, 1998, seven more bonsai from private collections in Japan were gifted to the U.S. National Bonsai and Penjing Museum in Washington, D.C. Saburō Katō made the formal presentation. Also added at this time was a magnificent Stewartia monodelphia forest planting which Katō had created with 39 trees on an American-made slab at the 1993 World Bonsai Convention. It was purchased by Bonsai Clubs International and donated to the National Collection. In November, Japanese Prime Minister Keizo Obuchi celebrated the visit to his country by President Clinton with a gift of a 250-year-old Ezo spruce bonsai ( Picea jizoensis Carr. ). The tree had been collected in the 1930s from Kunashiri Island by Tomekichi Katō and his son Saburō, and had been trained and nurtured for over fifty years by the latter. The following May Saburō was invited with three of his staff to accompany Obuchi to the White House. There the sensei had the opportunity to explain to President Clinton how he and his father had raised the Ezo spruce bonsai. This explanation made a deep impression on the president. (This Ezo spruce bonsai is currently on display at the Japanese bonsai pavilion of the U.S. National Arboretum.) 15 From 1999 through 2002, Japan Airlines sponsored an annual World Bonsai Contest. Saburō Katō was chairman of the screening committee. At the 1999 JAL World Bonsai Fair, Katō-san was given a Gold Medal Award from Rosade Bonsai Gardens by Mrs. Solita Rosade, President of Bonsai Clubs International. The award is given to the person who has contributed for promoting Bonsai culture worldwide.

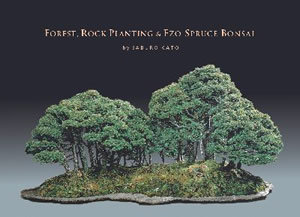

Saburō Katō was a participant and one of the interpreters at the 4th World Bonsai Convention held in Munich in early June, 2001. He also penned the preface to WBFF's Bonsai of the World II. A two-part article entitled "Mansei-en and the Kato Family" by Thomas S. Elias was published in BCI's Bonsai magazine throughout that summer. And the first English edition of Katō's first book Forest, Rock Planting & Ezo Spruce Bonsai was published by the U.S. National Arboretum. 16

In mid-May 2002, The Katō Stroll Garden was officially dedicated as part of the International Scholarly Symposium on Bonsai and Viewing Stones at the National Bonsai and Penjing Museum at Washington, D.C.'s National Arboretum. The garden, most prominently colored by maples and blooming azaleas, honored the five generations of bonsai enthusiasts of the Katō family in Japan who have done so much to promote the art throughout the world. 17

On May 28, 2005, the bonsai world gathered at the John Y. Naka Pavilion of the National Bonsai and Penjing Museum in Washington, D.C. as part of the World Bonsai Friendship Federation's Convention to commemorate John's many contributions to bonsai. An impressive film was shown about Saburō Katō and the late John Y. Naka, paying tribute to these two men for their historic work in founding the WBFF, which is dedicated to promoting peace through bonsai. This opening session concluded with the ceremonial igniting of the Candle of Peace by Saburo Katō. The Convention ended the evening of Tuesday May 31 as Katō-san extinguished the Candle, which was conveyed to Solita Rosade who succeeded Felix Laughlin as Chair of the WBFF. 18 (A video shot in 2005 featuring Katō-san at Mansei-en can be seen here.) Graham Ross hosted a segment of the Australian Better Homes & Gardens television show with a visit to 91 year-old Saburō Katō in Omiya. The biggest and best collection of dwarfed potted trees in the world was shown, including a 2000 year-old [sic] Shimpaku Juniper. The episode aired June 16, 2006. That November, Mr. Katō held a special exhibition to commemorate his 90th birthday at the Ueno Green Club where he displayed many new bonsai creations. He had created over 500 forest compositions of all sizes and types in his lifetime. 19 ("Japanese Bonsai Masters" is found about 2/3 of the way down the page, http://www.j-bonsai.com/about.html, and is hosted by Yoshihiro Nakamizu. Shot in October 2007, approximately the first 20% of this video features Mansei-en with Katō-san.) On the morning of February 8, 2008, Saburō Katō died in Omiya. This was the day before the 82nd Kokufu-ten Bonsai Exhibition opened. It is believed that this grandmaster was the only person who had attended every one of the 80 Kokufu-ten (there was not a #19) to date. Mrs. Saburo Kato passed away on April 24, 2011 at the age of 87. 20 |