| 21 |

1947 -- Jerry Meislik was born in Czechoslovakia. [His family would immigrate to the United States

when he was very young. His interest in bonsai would begin as a teenager when he would visit the bonsai exhibit

at the Brooklyn Botanical Garden. He would receive a BS in Biology from

Brooklyn College in New York and graduate from medical school.

He would meet his soulmate Rhona while in medical school and they'd be married in 1970. (They would be together for the

next 54-1/2 years.) Then he would do his internship at Albany Medical College

in 1971 and would complete his Residency in Ophthalmology at University of Colorado Medical Center

in 1977. This would be followed by a year of Fellowship in Glaucoma at Bascom Palmer Eye

Institute in Miami. While living in Florida Jerry's interest would be re-kindled in bonsai after seeing some fabulous

tropical trees growing all around him, especially Ficus. Since then he would be actively studying trees and how to

grow them in containers and creating bonsai. He would be fortunate to have exposure to many excellent bonsai teachers, and

his knowledge would increase as he traveled to Japan, Singapore, Malaysia, Vietnam, Australia, New Zealand, Korea, Taiwan,

Thailand and Hong Kong to study their bonsai and design concepts. Dr. Meislik would be a Clinical Instructor in

Ophthalmology at the University of Michigan. He then would work at

Huron Ophthalmology in Ypsilanti, Michigan for twenty years. He would be Board Certified

in Ophthalmology and be a member of the American Academy of Ophthalmology. [Jerry would also be on the Board of Directors of American Bonsai Society (1989-1995), Chairman of the ABS Journal Editorial Committee (1990-1996), Board of Directors of the National Bonsai Foundation (1993), and Regional Editor of the National Bonsai Foundation. He would be an instructor for bonsai courses at Ann Arbor Public School Community Education Program, University of Michigan Matthaei Botanical Gardens, and Ann Arbor Bonsai Society. Upon his "retirement" to Whitefish, Montana he would come to work at Glacier Eye Clinic in 2001. His teaching of bonsai would continue at Flathead Valley Community College in Kalispell and he would be president and vice president of the Big Sky Bonsai Society in Montana. Jerry would write Ficus: The Exotic Bonsai (2004) and Introduction To Indoor Bonsai (2006), this latter based on many years of grown indoor and tropical bonsai under varying conditions including windowsill, greenhouse, and artificial illumination. This would be in addition to over fifty articles on various bonsai topics for the specialty magazines. He would be available to lecture, teach and demonstrate bonsai by appointment. His web site would be www.bonsaihunk.us/. In May 2022, some 150 of his Ficus trees would be acquired by Wigert's Bonsai Nursery in Florida. They would be available for sale after acclimization.]

Jerry & Rhona Meislik.

("Jerry Meislik - USA," http://www.bonsai-bci.com/bci-artists/145-jerry-meislik-usa;

"Dr. Jerry Meislik, MD," http://www.avvo.com/doctors/jerry-meislik-2101315.html;

"Profile: Jerry Meislik," http://artofbonsai.org/forum/viewtopic.php?t=368;

Jerry's

Facebook post, 05/20/22; Marty Klein's

Oct

9 FB posting of Jerry's

obituary.). SEE ALSO: Sep 28

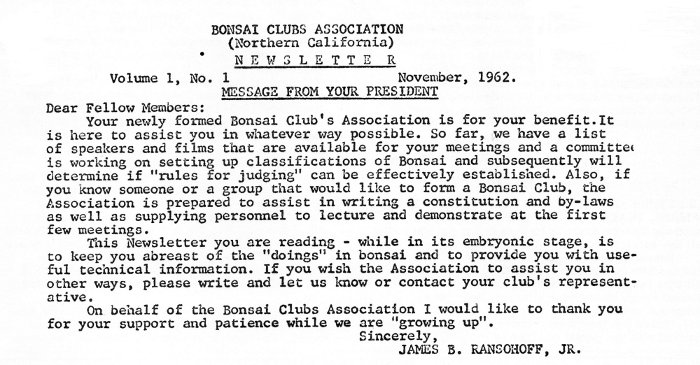

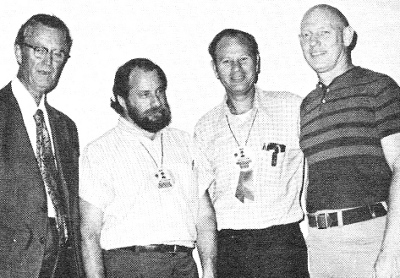

(Photo courtesy of Alan Walker, 05/11/07) 1974 -- The author, photographer, naturalist, and horticulturist George Frederick Hull died at age 65. (A 46-year staff member of the Chattanooga Times, his long career as its chief photographer and garden editor was interrupted only by his service in the U.S. Army during WWII. His photographs had been seen in such magazines as Life, Look, Time, and Newsweek, and he had articles on gardening in The New York Times, House & Garden, Popular Gardening, Horticulture, etc., and a magazine in England. His interest in miniature trees was aroused in the early 1950s when a reader asked him "Is it worth $10 for six packets of tree seeds and the secrets of bonsai in order to start a profitable business?" George doubted it, but pursued the answer with several trips to the Brooklyn Botanical Garden, to various growers in this country, and with his own efforts to grow plants. Trips to Japan (at least four) would deepen his understanding. He contributed to the Nov. 1962 inaugural issue of the "Bonsai Clubs Association Newsletter," the first English-language bonsai publication, which eventually became Bonsai Clubs International Bonsai Magazine (see below, "Also this month"). The year after a 1963 study trip was made to Japan, his book Bonsai For Americans was printed by Doubleday & Company, Inc. (His second and third books in 1967 and 1969 were on general gardening topics and were also illustrated by his wife and daughter.) George was a founding member of the American Bonsai Society, was a member of its first Board of Directors and served continuously as a Director until 1973. He regularly attended the BCI and ABS conventions.)

"'Bonsai Greats' at BC'73 Atlanta

George Hull, Chase Rosade, Jim Barrett and Jerry Stowell" (Bonsai Magazine, BCI, Vol. XII, No. 8, October 1973, pg. 7)

"George F. Hull at the Bonsai Convention, Pasadena, California,

("About George Hull" by Dorothy Ebel Hansell, Bonsai Journal, ABS, Spring 1975, p. 15, with photograph; "In Memory...George Hull,"

Bonsai Magazine, BCI, Jan/Feb 1975, p. 16; Hull, Bonsai For Americans, dustjacket notes; "Meet the Directors,"

Bonsai Journal, ABS, Summer 1971, p. 37, with another b&w photo) SEE ALSO: Feb 23, Nov Also

July 1974. Photograph by Donald Vining." (Bonsai Journal, ABS, Spring 1975, pg. 21, Fig. 15) 1981 -- Peter Ryan Neil was born in Glenwood Springs in western Colorado, on the western slope of the Rocky Mountains. [Throughout his youth the fantastic array of tortured and stunted trees surrounding his home would create a deep appreciation of nature and the resiliency of plants. With every hike he'd take into the mountains, Ryan's interest in plants and their resiliency would grow, increasing his curiosity and unknowingly establishing a foundation for his future. He'd be taking taekwando classes since he was eight, which would lead to many DVD viewings of the [non-taekwando] martial arts film The Karate Kid. One day Ryan became engrossed in a scene in which the karate master, Mr. Miyagi, is tending a small tree. Miyagi hands the pruning scissors to his student, and tells him to imagine the tree the way he would like it to be. Daniel, the student, is hesitant at first, but after taking a few tentative snips is clearly enthralled. [Fishing may have been Ryan's initial justification for exploring his backyard, the Rockies, but after a fateful encounter with bonsai at the annual town fair and mentor-to-be Harold Sasaki from Denver, the subject of his hikes and the path of his life would be changed forever. One important aspect of the change was a Juniperus procumbens that he bought at a garden center in Glenwood Springs for $25 when he was twelve years old. (Ryan still has that tree today.) After passing the initial phase of excitement upon discovering bonsai, it wouldn't take long before he'd start exhausting his resources for self-study. Out of the blue a family friend would hand him an issue of Bonsai Today magazine that she'd find at a garden center. Ryan would start reading about the trees and try his hand at his first Ponderosa pine at 14 (which he would also still have in 2015). As he'd study up, Ryan would find an article on a famous Japanese bonsai master named Masahiko Kimura. In the time-honored world of Japanese bonsai, Kimura was an outlier; a radical who'd pushed his trees into dramatic shapes never seen before, with extreme, sculptural bends in the trunks and branches. The main article in that issue would show Kimura working on a cascading shimpaku. Ryan would be mesmerized by what the great Japanese master was doing with the tree and the manner in which he brought about such change. It would be like watching him sculpt a personality and give life to something already living, a second birth of sorts. Gathering back issues of bonsai magazines that contained Kimura's work, Ryan would become more and more enthralled with the way sensei was able to tease so much interest and expression out of a tree. Contrary to the sedentary image of a classical Japanese bonsai, Kimura's work would have life and vigor, it talked, and moved, and always would seem to tell a story (a theme his work maintains to this day). Like many other western bonsai practitioners, Ryan's mind would by Kimura's work be open to what a bonsai could be. To Ryan, these forms were magical, and he'd resolve to become Kimura's apprentice. An unfortunate injury would end his collegiate athletic ambitions and after that he'd actually started pursuing bonsai seriously. Serendipity would prevail once again. After graduating from high school, Ryan would know that an education in horticulture could only help his chances. He would go to major in horticulture at California Polytechnic State University in San Luis Obispo, California. During his college education, Ryan would spend most weekends traveling to Los Angeles or the Bay Area to seek out the answers to those questions he'd have about bonsai. Some would be answered, many not, but each trip would take him one step closer to getting where he wanted to be. Ryan's motivation for pursuing an education in Japan would not only be driven by the desire to become adept at bonsai, but also to gain skills, knowledge, and answers to questions he'd have a hard time finding while studying in the United States. On one such trip during his sophomore year, Ryan would have the pleasure of working with Japanese-American bonsai artist Ben Oki in his Los Angeles garden. Little would Ryan know the magnitude of this meeting, but after subsequent journeys to see Ben, Ryan would tell Ben of his dream. Ben would then be invited on a trip to Japan to see the prestigious Kokufu exhibition and to meet the man behind Ryan's inspiration, Masahiko Kimura. The American bonsai artist would then offer to introduce Ryan to Kimura, if Ryan could get himself to Japan. At this point, Ryan had accumulated some savings from cleaning offices, bussing tables and working for landscaping companies. So he would put aside his studies and set off with Oki. After touring several bonsai gardens, Ryan and Ben would finally approach what Ryan considered the holy land: Kimura's studio, in a small town outside Tokyo. Ryan would be struck by Kimura's power immediately. "He had an aura about him," Ryan would recall. "He really commanded respect. It was kind of instant humility for me. Apprentices were running around, predicting his every move and handing him what he needed without him asking -- and I wanted to be part of that." [On this particular day, Kimura would be restyling a 1,000-year-old spruce. To Ryan, the process would be "almost a religious experience." It would seem as though Kimura gave the tree a soul. At one point, Ben would find a chance to talk to the master in private and introduce Ryan as a potential apprentice. Kimura would laugh, for he was of no mind to accept another foreign apprentice. It would be no secret that the eastern and western mentality and way of doing things differed greatly and, at that time, Kimura would be very upfront telling Ryan he didn't think an American was capable or prepared to do what was necessary to study at his nursery. Ryan would be undeterred. He would remain determined to obtain an apprenticeship and make his dream of studying under Kimura a reality. After returning home, he would write Kimura a letter repeating his request to come study with him, but he'd receive no response. He wrote another letter, and again heard nothing. He would write Kimura a letter a month for two years with the intention of at least staying in his mind. A month or two before Ryan would graduate from college, Kimura would write him back with his first and only response. The master would apologize for his absent replies and note that he had been busy. He would say, "Stop writing letters. You're welcome to come try but don't plan on staying long. Try if you wish but failure is imminent." [And so, Ryan would be off to Japan, with limited funds and speaking no Japanese. After arriving, he would be given a small stipend for room and board, which would allow him to find a tiny apartment near Kimura's studio. Ryan would be the youngest and the only American out of six students, and he'd start at the bottom. After a few weeks, he'd realize that apprenticeship was much worse than he ever could have imagined. His duties would include scrubbing toilets, washing rags for hours at a low stone sink and weeding the lawn with tweezers. He would work a seven-day week, often till midnight, and then would have to clean the workshop before the older apprentices (senpai) arrived in the morning. When he did get a chance to be around the trees, "Mr. Kimura never explained a single thing to me. I didn't speak the language for two years, but I sat and watched him." His techniques were drastic, using heavy clamps that exerted thousands of pounds of pressure on unusually large, living sections of trunks and branches, radically altering the tree's direction. It would sometimes seem as though Kimura was brutalizing his trees. He was no Mr. Miyagi. Instead, he was a taskmaster who would blow cigarette smoke into Ryan's face as the student worked, telling him that if he weren't hard on him, he wouldn't remember the lessons. [Every apprentice would have a three month trial period, a wash-out phase of sorts where they would be tried and tested and all non-hackers weeded out. Those first three months would be the toughest three months of Ryan's life, but determination and desire to accomplish what he set out to do would prove to be the most important factors in securing his apprenticeship. Kimura's various apprentices would be keen to his every need and work in perpetual motion while the master would go about the task at hand. Discipline would be the foundation of his school of thought and no action wasted or done in vain. It would seem like every move he'd make would be conducted with one deliberate, calculated, and powerful stroke. After watching Kimura work for close to an hour Ryan could only begin to understand what being a master truly meant, but it would be enough for him to realize his nursery was where Ryan would want to be. For him the hardest part of the apprenticeship itself would be maintaining his mental composure under any set of circumstances and any working condition. When he would go home every night he'd be exhausted, but it wouldn't be because of the massive amount of physical labor, although there'd be a fair portion of that. Instead, there would always be a tremendous amount of mental pressure that the apprentices would have to deal with studying under Kimura and that would take its toll over time. It would be all part of his master plan to get them where they needed to be so that they could succeed in the world of bonsai. Ryan would complete six years of apprenticeship under the guidance of his world-renowned master. His time in Japan would be challenging and full of failures and triumphs. From the beginning Kimura would tell him that being an apprentice is not about bonsai; instead it is a time to strengthen your heart and become a man. It was true that he would not go easy on his students and his methods of teaching and inducing growth in his pupils would often times take a lot of reading between the lines to understand what it was that the master was trying to tell them. A bonsai apprenticeship, if you last, would go on for about five years, though it'd be up to the master to decide when you have completed your training. [Ryan would learn a lot by failing. "I would see my master doing groundbreaking work," he'd remember, "and I would go home and buy a very inexpensive tree and I would apply the technique. I had a freezer box, and by the end of my apprenticeship I had a freezer full of 76 dead trees. That box was my learning curve. No one who's ever going to be proficient at bonsai is going to do so without killing a tree." Ryan would soon learn that the horticulture was one thing, the artistry quite another. "The first two or so years of my apprenticeship was 90 percent of what I needed -- the technique," Ryan would say. "The remainder [another three years] was the last 10 percent -- understanding how you achieve interesting design." During his fifth year in Japan, Ryan would begin to think about what an American style of bonsai could be, and the idea would take root. He wouldn't yet be sure of its form, but he would know it should represent something essential about American culture, as well as its environment. Part of what inspired him would be how unusually aggressive Kimura was with his trees, daring to push them in directions they would not otherwise go. There was a boldness in Kimura's style, which he began to think might work well with the boldness of the American landscape. After his five-year apprenticeship, Ryan would spend an additional year working for Kimura -- a way of repaying your debt to your master. Kimura would never soften, but he would treat Ryan less as a student and more as a peer. Occasionally, he'd even ask Ryan's opinion. But, in the end it would all lead down one yellow brick road, so to speak; he would be simply teaching the students how to think and how to use their heads to solve problems before they approached a task with their hands. Ryan would have learned more about how he thinks, how he learns, and how he goes about improving himself than he would have learned about bonsai. However, he would have managed to pick up a fair amount of bonsai knowledge along the way as well. As apprentices the students would be responsible for all the trees at the nursery, including clients' trees (the majority of plants there) which would be treated no better nor worse than Kimura's personal trees. They would be all handled with the same amount of attention and dedication. Even on his days off Ryan would find himself gravitating to his own small collection of trees on the balcony of his apartment, as if visiting friends or watching over a child. Bonsai would become a habit, a lifestyle, something he would later do without thinking about. One of the most important aspects of his apprenticeship would be the idea of being part of a select group of individuals that were able to fully grasp what it was Kimura would be trying to teach them, and who would value that knowledge enough to honor the tradition of remaining close to their master. All of Ryan's experiences would allow him to grow and develop as a bonsai professional. [Ryan's objective upon returning to the United States would be to continue promoting the art of bonsai and more importantly help raise the level and knowledge of bonsai in America and abroad. In 2010, Ryan would return to the U.S, intent on starting a nursery unlike any other. Although he'd never set foot in Oregon, he would choose the state partly because just about anything can grow in its temperate, wet climate. (Oregon is often called the nursery capital of the world, and a single region near Portland -- the Willamette Valley -- would provide 85-90 percent of the stock to U.S nurseries.) He would invest cash and considerable sweat equity to turn a run-down, semi-rural property outside Portland into a fitting setting for his creations. He would carve a nursery space out of the forest, building bonsai display spaces and adding flowering ground cover and native perennials, all punctuated with full-sized specimen trees -- Japanese maples, dramatic evergreens, and a splendid flowering plum. But the main advantage to the area would be a ready supply of collected yamadori -- rough, scrubby-looking trees that would have the potential to become bonsai. Over the next three years he would acquire $1 million worth from a local collector. [Ryan would finance all this by teaching bonsai workshops around the country, which would keep him on the road nine months of the year. His first international demo would take place in 2010 with Marc Noelanders, who would have also previously studied under Kimura. Ryan would put into action the things he learned from his great master, and expand on them through the realization of International Bonsai Mirai outside of Portland, OR. In both 2011 and 2012 he would demonstrate at over a half dozen major national and international exhibitions and conventions. He would go on to be the subject of several articles and videos in Bonsai Focus (the successor to Bonsai Today), and numerous other videos of his demos and critiques would be posted on the Internet's World Wide Web. ["I don't want people to look at my trees and say, 'Oh that's nice,' Ryan would say. "I don't want the trees to be passive and quiet and reserved. I want people to actually respond." "I want people to say, 'Holy Shit!' Or 'I hate that! I'm trying to push the envelope. Nothing about Mirai is really that relaxing. These are pretty energetic trees." Ryan's long-time girlfriend Chelsea would also have grown up in that small Colorado mountain town. They'd be old-fashioned pen pals through college and afterwards. They would elope in 2012 and a year later have a son. Chelsea would be passionate about social and cultural justice issues. There'd be a lot of money coming into Mirai, but there'd also be a lot going out. When Ryan would start the nursery, he'd handle the business side of it in "the typical artist's way of doing things," he would say. "It was a total shit show." Eventually, his wife Chelsea, an attorney, would quit her immigration law practice to help Ryan as Director of Operations at Bonsai Mirai. But the economics of bonsai would be challenging. To balance the books, Ryan and Chelsea would have to turn their bonsai interests into a multi-faceted business. They would sell trees, teach, consult, and even offer a kind of tree day-care service, boarding other people's bonsai and providing maintenance. For a skill as rarified as bonsai, these services could be lucrative. On the teaching front, for example, Ryan would typically have about 80 students who'd pay between $1600 and $2400 a year for the privilege of spending several days at Mirai during periods when the trees would need a lot of work. Then there would be Mirai's sales, which would average 20 to 30 trees a year, with prices ranging from about $1,200 to tens of thousands. On the other side of the ledger, Ryan would admit, "our overhead is very high. We've already spent about $45,000 on pots this year. I think we showed a profit for the first time last year, our fourth year in business." [In 2015 Ryan would then reduce his travel for conferences and workshops to about four weeks a year. He would want to see American bonsai embrace the energy and diversity of the American landscape. To do that, he would want bonsai artists to use "trees collected from the harsh conditions of America's mountains, deserts, and coastlines." In his opinion, this would give bonsai artists a mostly untapped opportunity to bring out "the unbridled" quality of American trees through "asymmetry and dynamic movement." And that, Ryan would argue, would give bonsai a kind of wildness that "speaks to the freedom in American culture." To that end, Ryan and Chelsea would combine have combined energies with Michael Haggedorn and others for a few years to put on The Artisans Cup exhibition at the Portland Museum in late September 2015. [RN - "I hope bonsai evolves to something beyond "bonsai" and into something identifiably American in form and context. We cling to this notion of bonsai as something that is only bonsai if it is authentically Japanese. As we continue to evolve and use our natural surroundings as a reference, bonsai has no choice but to turn into something else as an iconically American art form. Someday, I see a moment where our rendition of bonsai is called something else entirely." [CN - "I hope for a new generation of bonsai artists and practitioners across the world to approach the art with introspection, reverence, and, most importantly, a strong horticultural foundation. I hope that we will continue seeing bridges crossed between cultures, and egos dismantled, so that bonsai can truly become a diverse, cultural representation of nature in miniature."] [Ryan would make this excellent interview with Bill Valavanis before the start of the 6th U.S. National Exhibition in September 2018. Mirai videos on YouTube, starting especially at the time of the Artisans Cup, continue to be outstanding sources of information on many, many levels to all enthusiasts. Ryan's teaching skill smoothly shares the botany and horticulture, physics and engineering, cultural and aesthetic appreciation, design and vision required for bonsai. See this recent video as an example, as well as this interview where we can see how he is possibly the world's finest interpreter of bonsai culture and potential. And this 2022 New Yorker magazine article about Ryan's apprenticeship under Kimura. Note: there is some controversy about the exaggeration or accuracy of a few sections and quotes in this article based on five-year-old interviews. This podcast from July 26, 2023 about his "Top 5 Transformative Bonsai Books" is an awesome insight into Ryan's perception of the world of bonsai. Australian Lindsay Farr would be interviewed by Ryan in an excellent two-part July 2024 podcast conversation for Bonsai Mirai which explores both of those artists, as well as Ryan's sensei Masahiko Kimura. Part 1 can be heard here. With many awesome insights about teaching, spirituality, and similar esoterics about bonsai, Part II can be heard here. Ryan's master class in tree design is presented in the continuing of the process of tree design from Bonsai Techniques II in a two-part late January 2025 video, "John Naka Juniper Restyling Pt. 1: California Juniper Transformation.")

RJB and Ryan at the ABS/BCI Convention in Denver,

(Conversation with Harold Sasaki by RJB and Ryan's business card given to RJB with birthdate added at Bill Valavanis'

insistence, both 06/24/2012 during ABS-BCI Convention in Denver; "Profile: Ryan Neil,"

http://artofbonsai.org/forum/viewtopic.php?t=3860; "The Story of the Mind

Behind the Mirai," http://www.bonsaimirai.com/about/the-story-of-the-mind-behind-the-mirai/;

Ryan Neil posting on Facebook, June 22, 2015; LeBrun, Nancy "The Bonsai Kid, A young Oregonian believes that he can create a uniquely

American form of the Japanese bonsai tree. And he is literally betting the farm on the idea that if he builds it, they will come," Sept

17, 2015, http://craftsmanship.net/the-bonsai-kid/; "Patrons of American Bonsai: Ryan & Chelsea

Neil," September 14, 2015, http://www.theartisanscup.com/blog/patrons-the-neils,

which includes the above final two quotes)

SEE ALSO: Mar 31, Apr 25, Jun 22, Jul 8, Sep 25, Dec 29

June 24, 2012 (Photo by Kenny Asher) 1998 -- Dr. Stephen K-M. Tim, a senior botanist at the Brooklyn Botanic Garden and an illustrator who was a guiding force for many of the exhibits and publications of the BBG, died at New York University Medical Center in Manhattan of cardiac arrest at age 61. (Born in 1937 and reared in South Africa, Tim received his doctorate in botany from Rhodes University. Tim had once nurtured fine bonsai in a <50 sq.M. hothouse in the Bertrams (the oldest suburb of Johannesburg). He, his brother Peter, and Douglas Hall were among the original Bonsai Gurus of South Africa. Later, director of the BBG, Elizabeth Scholtz, a fellow South African, hired Tim in 1971. He became the BBG's vice president for science, library and publications. He was described as an institution unto himself for his expertise in poisonous plants and for his popular educational programs for the public. Tim oversaw the launching of the garden's award-winning series of practical gardening handbooks and the opening of the Steinhardt Conservatory, for which he designed state-of-the-art plant displays. His illustrated worksincluded The City Gardener's Handbook from Balcony to Backyard by Linda Yang (1990 and its revised editions in 1995 and 2002), the BBG's 1995 article "Spiranthes cernua odorata 'Chadds Ford'" by Barry Glick, the BBG's 1998 article "Goldenrods -- Three Cultivars to Set Your Autumn Garden Ablaze" by Stephanie Cohen, and the book Stalking the Wild Amaranth: Gardening in the Age of Extinction by Janet Marinelli (1998). Tim was co-editor with Marinelli for The Brooklyn Botanic Garden Gardener's Desk Reference, also published in 1998. In addition, he wrote the brochure The Fertile Crescent: Plants of the ancients, an exhibit and symposium presented by Brooklyn Botanic Garden, February 9 to March 25, 1979, and the chapter on "Resting Periods, Light Effects & Indoor Bonsai" in the BBG's 1990 Indoor Bonsai handbook, edited by Sigmund Dreilinger (plus subsequent revised editions through 2002). [A botanical art exhibit of Tim's work would be presented in September and October 2001 at the Highstead Arboretum in Redding, CT. And in 2009 the Brooklyn Botanic Garden Auxiliary Cookbook would include some of his botanical artwork. The Stephen K-M. Tim Trail of Evolution -- on a continuous panel and illustrated with live plants -- would trace the history of plant evolution and the effects of climate change over 3-1/2 billion years. The Trail would be part of the Steinhardt Conservatory Greenhouse complex. Also part of that complex is the C.V. Starr Bonsai Museum and its historically-important collection.] (Fountain, Henry "Stephen Tim, 61, Plant Expert At Brooklyn Botanic Garden," NY Times, November 29, 1998, http://www.nytimes.com/1998/11/29/nyregion/stephen-tim-61-plant-expert-at-brooklyn-botanic-garden.html; Shin, Paul H.B. Dt. Stephen K-M Tim," November 26, 1998, http://www.nydailynews.com/archives/news/1998/11/26/1998-11-26_obituary.html; May 17th Comment to http://66squarefeet.blogspot.com/2010/05/native-plants-in-may.html; Hall, Doug and Don Black The South African Bonsai Book (Cape Town: Howard Timmins Publishers, Ltd.; 1976, 1983), pg. 17.) SEE ALSO: Sep 17 |

||

| 22 |

1930 -- Barry James Iles was born in Benalla, Victoria,

Australia. [Barry would be introduced to bonsai by his grandmother who'd gift him one as a child.

Barry would grow up with his cousin

Glenda Raymond (1922-2003)

who would evolve into an international performer. Their circumstances would be modest. Barry would go

to NY to study singing (possibly at Julliard) in the

1950s, but after 12 months would arrive at the realisation that he while he was a decent singer, he would never be

an elite performer. On his return to Melbourne, Barry would open a restaurant, and then would find his niche

in real estate. He would become quite successful. Matthew Iles would join the family business --

Barry & Matthew Iles, Hawthorne, Victoria, Australia -- in March 1980 and

would be involved since in retail, commercial and residential sales and leasing combined with site acquisition,

property development, feasibility analysis, research, performance reporting and asset management. Throughout the 1960's, 70's, and 80's Barry would be a dominant force in and generous in his support of the emerging Melbourne bonsai community. In a time when that community would be frugal in spending, Barry would rule the roost. A successful businessman with a passion for bonsai, his support would be vital in the establishment of the bouyant Melbourne bonsai scene we would know today. Barry wouldn't drive his Bentley past a bonsai nursery without making a substantial purchase. He would be a great friend of local bonsai pioneer, Max Leversha, and Max's touch would make Barry's collection very note-worthy. His collection of trees would be expansive, with probably 200 specimens ranging in size from tiny to huge. Barry would be a businessman with an artistic bent. Local bonsai nurseryman Lindsay Farr would recall that in the 1970s, a famed Japanese bonsai master would create a tray landscape at a local convention. Barry would not be in attendance for the actual demo owing to his business commitments that day. The landscape would be, at best, bland. The assembled members of the bonsai community would be certain that Barry would be the winning bidder when the work was auctioned afterwards. When he arrived, however, he would take one look at the work and announce his disinterest. Barry would be a creative man with a resolute knowledge of what he liked and what he didn't. At 6 foot 6 inches (just under 2 meters) tall, Barry would be a man of means and flamboyant style. Sadly, Barry's collection would be devastated by a system failure that occurred on Black Saturday. (The Black Saturday bushfires would be a series of bushfires that ignited or were burning across the Australian state of Victoria on and around Saturday, 7 February 2009 and would be Australia's all-time worst wildfire disasters. The fires would occur during extreme bushfire-weather conditions and resulted in Australia's highest ever loss of life from a bushfire: 173 people would die and 414 be injured as a result of the fires. As many as 400 individual fires would be recorded on 7 February.) After the Black Saturday fiasco, Lindsay Farr would offer to help Barry salvage the remnants. From then on, he would spend time in the garden with him and their relationship would evolve. The conversation course would turn from material to spiritual. Lindsay would see Barry often over the next few years. His Bentley would be replaced by a handicap buggy. Barry would drive that buggy with the same flair and aplomp that he rode the Bentley.

"Barry Iles, from Lindsay Farr's Facebook posting 08-12-17"

(Facebook posting by Lindsay Farr, 08/12/17; emails from LF to RJB answering questions, 08/14/17, 08/16/17,

08/19/17; email from Matthew Iles to LF and forwarded to RJB with a few minor corrections, 08/25/17.)

SEE ALSO: Jul 13

1947 -- Craig Coussins was born in Scotland. (His parents were both musical and his grandfather Louis was a soft shoe shuffler on the music hall stage from the late 1890's with Fred Karno and following the war, to the early 1920's. His mother was a well-known dance teacher for over 65 years and Dad was a dance band leader from the 1930's. Subsequently, Craig and his brother Ray loved music and dance and played a variety of instruments. Ray was a very talented child pianist who started playing with the Scottish Philharmonic at age 9 and was one of the youngest LRAM's (Licentiate of the Royal Academy of Music) in the country. Ray would pass away in 2023 at age 82.) [Craig would first see a real bonsai in a flower shop window in 1972 and would start growing these a year later. A meeting with the UK's leading master at that time -- Peter D. Adams -- in 1977 would lead to regular studies under Peter through 1991. A 1500-km round trip would be made every month from Scotland to so study, often returning with a new bonsai that Peter had gotten for Craig from a dealer in Japan. Craig would attend workshops at Peter's where he'd meet many other enthusiasts who'd become great friends over the years such as Dan Barton, Harry Tomlinson, and many others. (There were others prior to Peter who'd sell bonsai, though, but it would be a very small group who'd start Bonsai in the UK. It'd be the Bristol Bonsai Association and Dan Barton who would create the first really big effort in Bonsai, publishing booklets each quarter, sometimes more. It would be that group to which Peter Adams would belong.) Craig would begin teaching in June 1978 when he would found the Scottish Bonsai Association. A year after the first UK Bonsai Convention (1981), he would be a founding committee member of the Federation of British Bonsai Societies (FoBBS), along with Bill Horan of the British Bonsai Society and other worthies of the time. Meeting with grand master John Yoshio Naka in 1984 when the latter would come to Edinburgh (video © Craig Coussins), Craig would also study with Naka-san at the latter's home in Los Angeles. Craig would always be a fan of workshops as opposed to the theatricality of the convention demo. Even John Naka could not really see the point and would comment on his five-city 1984 tour that most of those demo trees would end up in the wrong person's hands and would die. (At least the Edinburgh demo forest would still be alive and under the care of Peter Chan to the present day.) Peter Adams, a prolific writer of Bonsai Books, would have started importing trees for customers. Peter's first book in 1978, Successful Bonsai Growing, would become the bible for all of the enthusiasts and students as that was geared to what they'd want to know. [A Scots pine (Pinus sylvestris) mountain-collected in Scotland in 1978 would be designed by Craig in the southern Chinese penjing style and would be presented to the people of Xian by its twin city, Edinburgh, eight years later. Craig would have used his own martial arts studio as a meeting room for workshops, bringing up many of the leading bonsai teachers of that time -- Adams, Tomlinson, Chan, McNeil, Barton, and many others. All at his own expense with little contributions from the folk attending. It was not about money but about learning. Craig was made honorary President of the Scottish club before he would leave in 1987 to take up work in London and Russia until 1991. He would gift his very large collection of books to that club before he'd leave. He would arrange the installation of the first National Collection in Edinburgh and help his friends Hector Riddell and Ian Bailie come up with the plan and build. (It would be later moved in 2011 to another friend's at his wonderful Peony Nursery.) [Craig would have a business of making ballet shoes in Moscow for a time and also learn to speak Russian then. His great grandfather and his brothers had emigrated to Scotland from Russia in the late 19th century. As a ballet shoe designer, Craig would be very familiar with Russian history, culture, writers, and music. He would meet Tamara Belousova, who for the past decade would have been working with the 44 Japanese Embassy-gifted bonsai at Moscow's Main Botanical Garden of the Russian Academy of Sciences. At first, Craig would be extremely surprised that there'd be people in Russia who'd have not only heard the word bonsai, not only knew the meaning of this word, but would also have tried to grow trees themselves. Craig would then make significant contributions by coming to the Garden on weekends and hold meetings, seminars, lectures, and practical classes for enthusiasts who'd have already appeared by that time, many in response to television programs and Tamara's articles in magazines about the collection there. [Although Craig would be honorary President of the SBA, he'd make the error of thinking that as the founder and benefactor to the tune of many thousands of GBP, and as Hon. Pres, he could make comments when he'd feel the need to do some very gentle questioning about the direction the group would be taking. He would want a federation of Scottish Bonsai Clubs with each having their own membership fees, powers, etc. and coming together to organise visits from masters on tours. He'd be shot down by a letter from the secretary and told that he would no longer be welcome in the SBA and that he should keep his nose out of their affairs. The result was that although Craig would return to his homeland Scotland in 1991, he would not have taught Bonsai at any SBA club since 1990. Meantime, beginning in 1992 he would write five books, head up nine conventions worldwide, and undertake numerous tours of America, Australia and New Zealand, Russia, Europe, and Singapore. He would become known in international circles as a Bonsai Master. Sadly, Scottish Bonsai at the time would be mired in their own version of politics by a small group of people who, for some reason, would not want him around. He'd seemingly be a persona non grata. Craig still would have a number of great Scottish colleagues like the amazing talented Robert Porch who'd come with him to workshops both in England and overseas. They'd also appear together at the European Bonsai Association (EBA) Convention in Bruges, Belgium in 1997 as well. At the regular workshops in his Bonsai Garden in Glasgow, he'd have many bonsai masters coming to work with him on his own collection including many great masters from England, Wales, Japan, China, Argentina, America, Canada, France, Italy, Spain, South Africa, Australia, and New Zealand. All places that Craig, in turn, would have been to to give classes. Although he'd make the offer to the then leader of the group, few Scottish enthusiasts came to meet those masters. He'd also organise three Scottish Bonsai conventions which were attended by visitors from across England, Wales, Ireland, and Europe. And of the many hundreds of interested people from far-flung places like Russia, they would include an attendee who would become his wife, Russian photographer Svetlana Novikova. [Craig would write for many bonsai magazines around the globe. His books would include Bonsai for Beginners (2000), The Practical Guide to Growing Bonsai (2001), the multi-contributor and heavily-illustrated works The Bonsai School (2002, for which RJB would be asked to contribute to the history sections, along with two dozen other international artists), Bonsai Master Class (2006), and The Handbook of Bonsai (2007, derived from his first book). Craig would also love singing bowls, Native American flute, Jazz, opera, the design and creation of various types of dance shoes, photography, suiseki (a collection of over 1,000 pieces would be amassed from around the world), and Chinese and Japanese gardens. Craig's web site would be http://www.bonsaiinformation.com/.] [In early August 2011, Craig would announce that his bonsai collection of over 60 specimens, including a number of large yamadori medium-sized bonsai and shohin, was being put up for sale so that he could focus on his suiseki and scrolls business. In 2022 on his Nik Tokonoma Facebook page, Craig would post a twelve-and-a-half minute long slide show of some of his travels to China. His visits a decade earlier to the Shanghai Botanic Gardens, Suzhou and Brook Zhao's gardens would capture "a little of the landscapes, people and culture of this vast and beautiful country." And later in the year he would re-share this thirty-eight-and-a-quarter minute slide show of many specimens in his viewing stone/suiseki/gong shu/Chinese scholar stone collection from 2018.]

Craig Coussins, with his wife Svetlana and her first UK bonsai,

(Craig Coussins in e-mail to a group of friends, including RJB, 27 Nov 2007; while much of the above

information was originally found on the following web sites, the dates used above are corrected to

match info from the back inside dust cover of Bonsai for Beginners, plus "About the Author,"

from pg. 9 of his book Practical Guide (although that one book plus its back inside dust cover

give 1981, 1982 and 1983 as the founding dates for FoBBS); "Craig Coussins,"

http://www.psba.us/coussins.html;

http://www.bonsai4me.com/Gallery/GalleryCraigCoussins.html;

http://www.suiseki.com/collectors/craigcoussins.html;

http://home.comcast.net/~p.wehr/bonsai/CCoussins.html;

Coussins, Handbook of Bonsai, pg. 9; Nik Tokonoma Facebook posting, Sept 3, 2017; Nik Tokonoma

April 20, 2018

Facebook posting; Nik Tokonoma

December

13, 2020 Facebook posting;

http://ibonsaiclub.forumotion.com/t7423-craig-coussins-bonsai-collection-for-sale;

Tamara Belousova to RJB Facebook Messenger December 18, 2024) SEE ALSO: Jan 4, Mar 2, May 12, Jul 15, Nov 24, Nov 26

a Japanese Gray Bark Elm (Zelkova serrata), after having grown bonsai in her native Russia. ("About the Author," The Practical Guide to Growing Bonsai, pg. 9 and a December 13, 2020 Nik Tokonoma Facebook post) 2012 -- Masahiro "Masa" Furukawa died two months before his 69th birthday. (He had been one of the Pacific Northwest's first Japanese-trained bonsai artists, saikei master, and beloved Portland, OR-area teacher who was very active in the Bonsai Society of Portland (BSOP). Born in Nagasaki, Japan, he attended University of Agriculture and then apprenticed under Bonsai Master Toshio Kawamoto for ten years at the latter's Nippon Bonsai-Saikei Institute. Masa went on to found the Fujinomiya Bonsai-Saikei Institute, just to the southwest of Mt. Fuji in central Shizuoka Prefecture. Moving to the United States, Masa then founded the Oregon Bonsai-Saikei Institute and Japan Bonsai. He was instrumental in the BSOP and bonsai in the Pacific Northwest in general. Many of his bonsai are still sitting on benches in and around Portland and many in the society consider him their first sensei.)

"Masa Furukawa Shore Pine at the Pacific Rim Collection"

(Andrew Robson in Facebook post on November 21, 2024) SEE ALSO: Jan 5, Feb 24, Nov 22

(Photo from Jeffrey Robson FB post Aug. 2, 2024) 2015 -- In concert with the "All India Bonsai Convention & Exhibition" in Vadodara, India, the first Black Scissors Community (BSC) meeting was held. The attendants were the Indonesian Bonsai Artist Community (KOSBI) Bonsai Sister Community members and other Black Scissors fellows from Indonesia, China, India, Vietnam, Australia, UK, Argentina, Venezuela, Colombia, USA, Japan, Poland, and Africa. The BSC is a multi-dimensional spirit in any positive aspects in any perspective. It is the symbol of new worldwide bonsai culture movement. The BSC remain as an informal "young generation" community to keep the dynamism and avoid unnecessary overlapping, duplicating or competition among existing organizations. Its mission is to promote the spirit of inclusive and respective bonsai sisterhood, spirit of enthusiasm to explore new ideas, spirit of freedom to create and to express, spirit of motivation to encourage and to share creativity of bonsai art in order to lift bonsai art to higher level in a new perspective. The greeting sign of BSC is two fingers (index and middle) on one hand pointing to any direction (although usually downward). (In 2013, Chinese artist and organizer Su Fang had initiated the idea of Black Scissors in a dinner-table discussion during the bonsai exhibition in Malaysia. This was then adopted by Chinese-influenced Indonesian artist and author Robert Steven in his Indonesian Bonsai Artists Community (KOSBI) which was declared/launched during the "International Bonsai Art & Culture Biennale 2014" on October 21 in Yogyakarta, Indonesia with the KOSBI Bonsai Sister Community program. Despite the enthusiasm of a new bonsai generation for this new platform in accommodating their burning spirit, it was also realized there had been many questions about what Black Scissors was, what the mission was, was it an organization?, etc. So it was decided that it was time to "officially" define and announce to make this movement clear in transparency to avoid mis-perception and bias of this spirit movement.) Everyone can create their own Black Scissors motto, but should reflect the Black Scissors spirit and mission, such as: We Dare to Create, Creativity Changes the World, Sisterhood is Our Family, Freedom of Expression, Think Out of The Pot. Black Scissors Pro's are kind of advisors team from "young bonsai generation" e.g.: Sergio Luciani, German Arellano, Ofer Grundwald, Sanjay Dham, Matyie Che Makhtar, Tony Tickle, Nacho Marin, Jeni, Jun Ilaga, Chong Yong Yap, Masashi Hirao, Rui Ferreira and Erik Wigert. New Pro's can be added. See also this video of Robert Steven on Artistic Bonsai Presentation. [In 2016, there would be four Bonsai events that would be supported by BSC: National Black Scissors Exhibition, in April in Manila, Philippines; International Black Scissors Bonsai Convention, 02-04 September in Alytus, Lithuania; National Black Scissors Convention & Exhibition, end of September in New Delhi, India; and the 1st International Black Scissors Conference in China during the 2nd week of December. In 2017, a 2nd International Bonsai Art and Culture Biennale & 2nd International Bonsai Creation Conference would be held in the Philippines, supported by BSC. Any organization or club could apply to host a national or international Black Scissors event or to be supported.] ("What is Black Scissors?" Facebook posting by Robert Steven, https://www.facebook.com/robertbonsai/media_set?set=a.10207268857454252.1073741866.1068980522&type=3&pnref=story; Corrections and clarifcations by Robert Steven on Dec. 11 to William Valavanis' posting on Facebook the day before.) SEE ALSO: Jun 25, Dec 7 |

||

| 23 |

1962 - Caroll Dewar was born in Johannesburg,

Gauteng, South Africa. [She would attend Hoërskool President

High School for five years till graduation in 1980. She would have a few jobs over the next three decades

-- the first half of which, of course, would be during the final days of

apartheid in her country. In 1980 a close friend who was

terminally ill would give her his baobab bonsai to care

for. She'd kill it by overwatering it, but get the bug and start bonsai on her own. This would also be

the start of her love-hate relationship with baobabs. In her early days with bonsai she would belong to a club,

but the true sense of creating would only start after she had left the club scene and could create with abandon, no

longer bound by the unbending rules of the classic art of bonsai, or the pressure of criticism by others. She

would stop exhibiting at bonsai shows, but would open her house to garden clubs and friends and love sharing her

personal bonsai art with them. Her garden or En with over 400 potted dwarfed trees in it would also be

complimented with a koi pond. Her favourite bonsai style would be the

literati because she'd see so many natural

examples around where she lived. In 2003 she would suddenly get very ill with an original diagnosis of

Lupus. This more recently would be

clarified as Rheumatoid

Arthritis. This would interfere with her piano-playing and pottery-making, but bonsai would continue to

provide her with a creative outlet. [Caroll would later say in an interview: "I make trees in memory of people. When my Gran died, I made her a tree, same when my brother and father died. I also make trees for happy occasions, like when my [three] sons [with gym-owning husband Steve Hermann] were born, I made a bonsai for each of them. So, bonsai helps me to heal and remember and celebrate. The term 'Bonsaichology' really started off as a joke. One night, my kid called me a 'bonsai-chologist' -- or was it 'bon-psychologist'? I can't remember, but I do prefer the first one." In 2010 Caroll would start a continuing interest as a freeland action sport photographer. From April 2010 to March 2011 she would qualify as a Clinical Psychologist and work for the Department of Health at the Eshowe Hospital, Eshowe, KwaZulu-Natal. She would be a Senior Clinical Psychologist at Eshowe from April 2010 to May 2011. In 2011 the Head of the Department of Psychology at the University of Zululand would phone her and offer her a job at her old alma mater. In 2012, she would start planning on doing her PhD on the Rorschach test, but her promotor would advise her to do something that would not take so long. He would ask her what she was passionate about, and bonsai would immediately came to mind. From there, the topic would develop, Bonsaichology would grow, and she would complete her PhD in a record time of eighteen months. It would take another year to find suitable examiners as Ecopsychology -- which is working in nature with nature and people -- would be fairly new, and bonsai as a therapy tool would have never been heard of. Caroll would think that it would be wonderful to share with people what bonsai meant to her, and how it would have helped her through some very difficult times in her life. In 2013 she would submit a thesis, "Integral Ecopsychological Investigation of Bonsai Principles, Meaning and Healing," in fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of Psychology at the University of Zululand. She would have used information from 253 international bonsai artists and conducted in-depth interviews with 40 of them on how bonsai "saved" them. The participants, all well-known bonsai artists, just never formally thought of bonsai in a healing light before. It was incredible to be trusted with their stories. Caroll would state, "Even now, I still have contact with some of them, and we still communicate about how bonsai helps." (Four of the sources referenced in the thesis would be from this website, in fact.) In 2014 she would also deliver a paper at an international psychological conference in Osaka, Japan on bonsai as an art therapy tool. She would be a Senior Lecturer at the University of Zululand, and would be acting as Deputy Dean -- Research and Internationalisation, Richards Bay, KwaZulu-Natal, with a limited private practice as a clinical psychologist. [In addition, from December 2010 to the end of 2014 Caroll would be Editor of the on-line Bonsai in South Africa Magazine, from her home in Mtunzini, KwaZulu-Natal. (At least one article being reprinted from this website with permission.) In mid-November 2017 she would be elected as president of the South African Bonsai Association. ["After my thesis, one of my examiners contacted me and asked me to write a book, a kind of self-help art therapy book, and that is what I'm busy with now. Bon-saichology just grew from there and is now my trademark. There are even some revered bonsai people in Australia who are openly using 'Bonsaichology' (with my permission, of course). I just love the idea that it is being taken seriously by big artists... In any case, I now have a registered research project, on my second three-year cycle. My first group was with 30 traumatised youth from Dukuduku in KZN, South Africa. I worked with them for a year. Currently, I am waiting for ethical clearance from the Department of Correctional Services to start working with juvenile offenders. I also have a small group focusing on bereavement. My next project will be using bonsai as a neurological rehabilitation tool." That resulted in a March 2021 publication of both "Bonsai as a group art therapy intervention among traumatized youth in KwaZulu-Natal" and "Practitioners' Experiences of the Influence of Bonsai Art on Health." Her website is https://bonsaichology.wordpress.com/. In October 2022 she would accept an Associate Professorship at https://www.nwu.ac.za/North West University, the Mafikeng campus, some ten hours northwest of her home. She would plan on going home every six weeks and having people on each end helping take of her bonsai.]

"Caroll and Reported First Bonsai in South Africa from Becky Lucas at Heritage Collection

(Caroll's Facebook page; "Caroll and Bonsaichology,"

Our Monthly Habit, Bonsai Addicts Newsletter,

May 2018,

Vol. 3, No. 4, pg. 2; "The Art of Bonsai as therapy for Arthritis," Joint Ability, The Arthritis Foundation

of South Africa, Winter 2015, pp. 3, 21.; emails with RJB Nov. 24-25, 2019; FB messenger w/RJB on Aug 25, 2022) SEE ALSO: Jan 25at the Botanical Gardens of Stellenbosch University, January 2019" (Photo from Caroll's Facebook pages) |

||

| 24 |

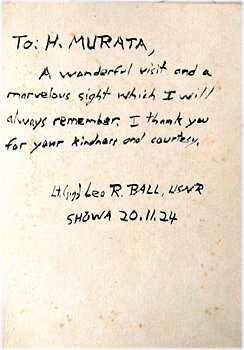

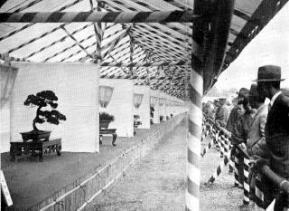

1945 -- A little-recognized but ultimately major turning point for the direction and fate of post-war Japanese

bonsai -- and thus for most versions of the art outside of China -- occurred today.

Kyuzo Murata was an Ōmiya bonsai nurseryman, co-inventor of the concave cutter

with toolsmith Masakuni I, and caretaker of the Imperial

Bonsai Collection. Because of health issues Murata had not been

drafted into the Imperial Army for the Pacific War

and was allowed instead, begrudgingly, to preserve many of the Ōmiya bonsai left behind by his drafted

neighbors. Because a large number of the Imperial bonsai had become collateral damage from the hot winds

created by last spring's Tokyo firebombings near but

not directly on the Imperial Palace and the past several years of

material and nutritional deficit were taking

a toll on him and his countrymen, 43-year old Murata was on the point of taking up some other occupation. The

loss of the war brought about many conspicuous changes at the Imperial Palace, and nearly everyone working on

bonsai there gave up their jobs. Bonsai pots lay around in the burnt-out sheds and stores; there was not a

pane of glass left in the greenhouse, and even the tools required for cultivation were not there. With the

Allied Occupation of his surrendered homeland came, among other things, a luxury tax on bonsai that was so high

that it nearly caused the disbandment of the returning growers at Ōmiya. However, on this particular

Saturday afternoon, fate intervened. A jeep containing Lt.(j.g.) Leo R. Ball, a graduate of the U.S. Navy Japanese/Oriental Language School, and John R. Mercier, a photographer with the military, drew up to Murata's Kyuka-en garden gate. They were horticultural enthusiasts who wanted to see the famous bonsai village. After they spent several hours in knowledgeable admiration of the beauties of the garden, Murata took out his Visitors' Book, which had been unopened in four years, and asked them to write in it. Both men wrote glowing tributes to the garden's beauty. [When Murata would have their inscriptions translated, the warmth of the messages left by his country's recent enemies would give him heart to carry on his work a little longer. Gradually, as more visitors came, he would begin to prosper.

Photo of this historic visit, with inscription stating (left to right)

Mrs. and Mr. Kyuzo Murata [as kanji], "keepers of the largest miniature tree garden in the world; Leo Ball, U.S.N.R.; Saito, an interpreter; Kenya Mitsuishi, chief boss of Omiya; and his screw ball [sic] brother-in-law." (Photo from Mercier's daughter, Helen E. Mercier Davis, to RJB 05/22/2022)

[In 1947, the Ōmiya Bonsai Association would be officially established with Murata as its first leader. The bonsai growers around Tokyo and Ōmiya formed regional groups and two or three times a month they would travel to the Imperial Palace in groups of seven to ten persons and try their best to save the withered bonsai from dying. The Tokyo Bonsai Association would hold regular meetings of their directors, do technological research, and only approach their task after scrupulous preparation. Murata would often be in contact with Toshiji Yoshimura, a prominent bonsai and suiseki artist from Tokyo. At one point, Murata's wife Fumi would introduce a lovely young local lady to Toshiji's son, Yuji. On March 11, 1948 Yuji Yoshimura, who would become "the father of bonsai in the non-Oriental world," and Miss Kazuko Nagano would be married. From 1949 to 1955, Murata would be chairman of the Nihon Bonsai Kumiai (Professional Bonsai Gardener's Association of Japan), determining how to maintain a supply of younger trees for the art after the ravages of the war on so many older specimens.] (Busch, Noel F., "The Lilliputian World of the Bonsai", The Reader's Digest, September 1967, pp. 185-186, which states that Mercier was "a newspaper correspondent from Washington D.C." but per Mercier's daughter, Helen E. Mercier Davis, in an email to RJB on 05/23/22, "He was not _actually_ a war correspondent, but was working for the military when he went to Japan during the occupation period. He took the pictures and kept the diary to send back to my mother. As to what he was actually doing, I'm not sure..." ; assorted material from Kyuzo Murata and Imperial Bonsai Collection articles; image via personal e-mail from Yukio Murata (Kyuzo's grandson) to RJB on 12/16/2004; The date "Showa 20.11.24" works out to be Saturday, Nov. 24, 1945, per NengoCalc; Note: at the 4:06 mark (through 4:23) in the Pacific Bonsai Museum's video "Hiroshima & Japanese Bonsai During WWII" from August 4, 2020, we see BOTH pages of the Visitors' Book, the left side being the comments from John R. Mercier which Yukio Murata did not send RJB.) SEE ALSO: Jan 15, Apr 1, Jul 7 2013 -- Peter D. Adams died suddenly but peacefully in his sleep. This was about two months after being hospitalized for a sudden onset of pancreatic cancer with blood and kidney infections while visiting some friends in the town of Farnworth, near Bolton, in Greater Manchester, UK. (Peter began his fifty year career with bonsai as a 12-year-old student at art school in England. After seven years at provincial college, he gained entrance to the Royal Academy Schools in London -- one of twenty-two admitted from several hundred applicants that session. After obtaining a post-grad degree in painting from the Royal Academy, he worked as a portrait artist, an advertising art director, animation filmmaker (including one about bonsai), in TV as film director, and illustrated for the UK Ministry of Defence. His own bonsai nursery and school were well known for thirty years and were attended by many of the prominent figures in European bonsai and visitors from around the globe. Peter exhibited annually with the Royal Horticultural Society in London at the world-famous Chelsea Flower Show and advised the RHS on the selection of judges for Chelsea in the subject of bonsai, after having received the gold medal there for several years. He also taught the staff of the RHS Gardens at Wisley as a foundation for their bonsai collection in Surrey. Adams continued painting and his work is in many private collections. His ability as an art critic led him to provide various art-related services for bonsai collectors everywhere. One form this took was instruction in bonsai design as a graphic program tailored to the needs of the individual and their trees. Part of this package was a very detailed future state tree drawing. These drawings were eagerly sought after for framing. He was also much in demand as advisor to private collectors of bonsai. Peter had to leave 40 years of work and hundreds of trees in England, including many famous trees. One red Seigen Maple from Nagoya he imported in 1970 and a raft Trident Maple were some of the best trees outside of Japan. A large portion of these trees are now in the National Collection in England. He had to leave everything because of USDA regulations which has a standing order not to import maples or two needle pines, of which he had many. One thing led to another, and he moved to the West Coast, Washington state. He vowed to never collect more trees, and instead to concentrate on easel painting. But then he was given gifts of trees in 2001 which started him building his collection to around 30 (or 70, if you asked his wife, Kate) or so trees. The decade hiatus was a watershed for this talented and productive man who now had a renewed manic enthusiasm and he felt like a novice again, this time in love with the small tree. Peter and Kate spent time traveling and teaching bonsai throughout the world. Peter authored nine books from 1978 to 1999 (with at least three translations into other languages), and two more in English later (in 2006 and 2007). His specialty was maples, the topic of three of the books, and his works included his own line drawings. As well as being a prolific western author of books on bonsai, he wrote for journals such as Bonsai Focus on a regular basis and also illustrated Kate's book Bonsai Easy Steps with 21 Species. His works have been a major force in the progress of western bonsai. He was a great inspiration to many bonsai artists over the years and trained almost everyone in the UK during the period from 1972 to 1992. In 2003 he was awarded the Most Prestigious Award from ABBA, the Association of British Bonsai Artists, for 'raising the Standards of British Bonsai to that of an art form.' One quote about Peter said it all: "there were no teachers till he became one and there were no books till he wrote one." He pioneered the Scots Pine as bonsai and was widely known for his work with Japanese Maple, Larch and Juniper. Under his unique tutelage where art and horticulture were so woven together, students who worked with him on the ongoing tree programs he generated, made rapid progress with their bonsai. As artistic expressions, his hand-drawn tree designs were recognized internationally as being among the best outside Japan and this quality he shared with his students. Coming from a fine art background set Peter apart and made his image-making fresh -- a fact appreciated by such giants in the art as Saburō Katō and Susumu Nakamura. His peteradamsbonsai.com website was in place by Feb. 2009, and his Bonsai Studio website was established in July 2012. A short video exists of his workshop for the Longview Bonsai Society in April 2013. He had originally been scheduled to do a program for the Bonsai Societies of Florida in November 2013 when his illness occurred. In very serious condition for a while, after a month he was transferred to a rehab unit and was to return with Kate to the States the beginning of December.) (Peter and Kate Adams Bonsai Facebook page, Nov. 26, 2013; Petty, Cheryl "Irasshaimase! Welcome to Peter Adams," Golden Statements, Golden State Bonsai Federation, Vol XXXII, No. 4 July/Aug 2009, p. 10; post by Fiona of message from Craig Coussins to Internet Bonsai Club forum, 12 Sep 2013, http://ibonsaiclub.forumotion.com/t14234-peter-adams-illness#146728; "Peter Adams -- USA"; "About Peter"; "Peter Adams Schedule"; "Bio"; "Services") SEE ALSO: Jan 4 |

||

| 25 |

|

||

| 26 |

1933 -- Tom Zane was born in Daytona Beach, FL. [He would meet a lady named

Sena in 1953 while both were studying at the University of Florida and marry her four years later. From

1955 through 1977 he would be in the Military Police Corps of the U.S. Army. In 1972, he and his family

would be stationed at Camp Zama

near Tokyo, Japan (for three years). During a courtesy call on a Japanese official with whom he'd work, Tom

would see a bonsai for the first time. A few days later he'd be presented with his first bonsai, a

five-needle pine. The Service Club there would be offering a 10-part course on beginning bonsai which Tom

would take. He and several others from the class would travel to the instructor's home and nursery for

lessons during the next two years orso. From 1977 through 1993 he would teach various criminal justice

subjects at Daytona Beach Community College.

He would found the Kawa Bonsai Society in Daytona Beach in 1978,

being its President and then Secretary and News Letter Editor for two decades. He would start teaching bonsai

classes in the late 1970s, writing and revising his own course syllabus as none were otherwise available.

After writing and publishing the Instructor's Manual for "Introduction to Bonsai -- A Course Syllabus" for several

years, Tom would create the "Introduction to Bonsai -- A Correspondence Course," donating the copyrights for both

to the American Bonsai Society. In addition to being on that body's

Board of Directors, he would also be on the Board for Bonsai Clubs

International. Tom would also serve BCI as a master of its website, manager of the audio-visual rental

program, 1st and 2nd Vice President, and President (1994-95), among other offices. He would write the

Bonsai Societies of Florida Convention Procedural Guide and the BSF

Guidelines and Procedures Manual and serve as a webmaster and editor for them. His

"Intermediate Bonsai - A

Course Syllabus" would be available on-line through the BSF. He also would volunteer locally, read

extensively and become a specialist in identifying and collecting forgeries of Japanese postage stamps.]

Tom Zane, 07/04/2002.

("Interviews,"

Florida Bonsai, Vol. XXXIII, No. 4, November 2003, pp. 6, 16, 17, 19) SEE ALSO: Apr 29,

Jun 7, Sep 15

(Photo courtesy of Alan Walker, 05/11/07) 1988 -- Andrey Levin, Elvira Mamedova, Valentin Rodionov, Marina Korosteleva, Vyacheslav (Slava) Pospelov, Alexander Vinyar (and possibly others) gathered at the Japanese Garden in the northern part of the Main Botanical Garden of the USSR Academy of Sciences on the northwestern side of Moscow in the Marfino District. This was where Tamara Petrovna Belousova, a career biologist who had studied Biology and Chemistry at Lenin Moscow State Pedagogical Institute, was working beginning in 1971. She had curated the bonsai collection there starting in 1981 when she was moved to another department and became the curator of the Ericaceae and Subtropical Plants of the Globe, Rare in Nature and Culture. Together with her colleagues, she would also develop expositions for the New Stock Greenhouse (her scientific work), which she would do until she left the Garden. This form of horticulture known as bonsai opened up a new universe for her of different traditions, aesthetics, and mentality. The 44 trees had been gifted from the Japanese Embassy in 1976. (This was the same year the 53 tree and 6 suiseki American Bicentennial Bonsai Gift was put on display in Washington, DC. The initiator of the gift to Moscow was the wife of the Ambassador of Japan to the Russian Federation, Mrs. Ayako Shigemitsu, but these specimens would be locked away -- after a two-year quarantine period -- out of the public view until the mid-1980s. Tamara's colleague, Vladimir Zhidkov, had taken care of the plants between 1978 and 1981. The bonsai were not masterpieces, but they were very decent plants, up to twenty or thirty years old. There were some very rare forms and they were all planted in real Japanese containers. Pines, Japanese and trident maples, azaleas, apple and plum trees, Pseudocydonia, a couple of groves -- pseudolarches and cryptomeria -- which were very neglected and remained so as none of the group had experience in forming multiple tree compositions. There were also several clumps of bamboo, Chinese elms, a rare enkianthus, a small and very slow-growing ginkgo, and a number of types of cypress. Bonsai is not a scientific direction and the Garden Management did not express enthusiasm about this -- as we've seen at a few other locations of collections. Gradually, a small group of amateurs began to form around Tamara and they were not discouraged by their inevitable initial failures with this art/hobby/way of life. There was essentially no literature, no tools, no knowledge, no stores, but there was a collection of bonsai, growing in the warm and sometimes very humid greenhouse. In 1985, Phyllis Argall's [otherwise historically unimportant] 1964 book Dwarf trees in the Japanese mode was then translated and published in Russian. Thus, Vyrashchivanie kaplikovykh derev'ev po iaponskomu sposobu would be that first Russian language text which provided instructions for cultivating bonsai. It would inspire many to take up bonsai as a hobby.) The bonsai group agreed that it was time to formally organize the first bonsai club in Russia. Tamara was elected as the first president, and she would continue in that post until her departure in 2011.

At the Stock Greenhouse of the Main Botanical Garden in Moscow, 1987.

[The Bonsai Club would hold its first exhibition of

trees the following summer. (This is why some sources say the club was formed in 1989.) Traditional Japanese music would be

played in the Garden. The atmosphere itself would be magnificent. There'd be many official guests, representatives of embassies,

Japanese scholars, and the main TV channels. The next day, the exhibition would be open to visitors, and people would come from other

cities. One or two exhibitions would begin to be held annually in the most prestigious premises of Moscow. The club would always

actively cooperate with the information department of the Embassy of Japan in Russia. All the events held would be of a joint nature

and with the Russia-Japan Friendship Society. Drawing information from a variety of sources and, most importantly, colossally expanding

the circle of communication and interaction with people familiar with the culture of Japan, Tamara would write a few articles on this topic.Tamara Belousova, curator of the bonsai collection, Ms. Ayako Shigemitsu, the ambassador's wife who initiated the gift of these trees in 1976, and Elena Golosova, curator of the just opened 'Japanese Garden' of the Main Botanical Garden of The Russian Academy of Sciences (Photo courtesy of Tamara Belousova) In 1990 she would travel to Osaka, Japan for the International Flower Exhibition held there. Mrs. Shigemitsu, with whom she was on friendly terms, would offer Tamara a private side excursion tour of Tokyo, accompanied by Mr. Shimoda, since Mrs. Shigemitsu would not be in the country at the time. (Of course, Tamara would warn the Russian authorities about this planned trip.) Shimoda-san would phone grandmaster Saburō Katō and they would first meet at the NBA in Tokyo, and the next day they'd be invited to Omiya. So Tamara would get to go to the bonsai village in Saitama and see the masterpiece trees there. Now, about this time bonsai teacher Craig Coussins of Scotland would be living and working in Russia. He initially would visit the Garden as a tourist. At first, he would be extremely surprised that there were people in Russia who'd not only have heard the word bonsai, and not only know the meaning of this word, but would also try to grow trees themselves. Craig would make significant contributions by coming to the Garden on weekends and hold meetings, seminars, lecture with slides on bonsai, discuss the state of bonsai in the rest of Europe, and give practical classes for enthusiasts who'd have already appeared by that time, many in response to television programs and Tamara's articles in magazines about the collection there. In 1993, the Bonsai Club in Moscow would host a grandiose event, the International Bonsai Symposium which was initiated by Craig a couple of years earlier. He would help in many ways in organizing this event. Other teachers present included Marc Noelanders and Erwin Verheyen (Belgium), Colin Lewis (UK), and Hatsuji Kato (Japan). On the opening day of the symposium, bonsai trees from the Garden's collection would be placed in the huge foyer of the main building of the Garden, and several specimens would be brought by Anatoly Annenkov. Anatoly was a well-known landscape architect who had first started with bonsai in the late 1960's. He'd see trees in the natural landscape of his native Crimean peninsula that were very reminiscent of the Japanese bonsai trees that he saw on postcards. And he decided to try to tame trees in bowls. In addition, the Sogetsu Club and Ikenobo would set up their arrangements along the massive staircase that led to the second floor, where there'd be a conference room and a lobby with a bonsai display. Many guests, climbing the stairs to the top, would note the sophistication of these works and the excellent threshold to the main action. Next to the foyer was a small winter garden, where the tea ceremony would be held by a branch of the Urasenke Group, headed by Mr. Nishikawa. There'd be many radio and television channels, including those from Japan. Then there'd be the official opening in the conference room, which would be attended by more than 300 people. The opening would be attended by officials of the city and the Ambassador of Japan to Russia, Mr. Edamura. After the official part, the guests would be offered an excursion to the Japanese Garden. Tamara would then attend the European Bonsai Assocation (EBA) conference in Bruges, Belgium in May 1997. She would continue to curate the bonsai collection until October 2011 when she'd leave for family reasons. A two-part video History of bonsai in Russia would be published in 2021, an interview of Tamara Belousova by Andrey Bessonov. (Part II is here.)] ("Adventures of bonsai in Russia by Alexander Vinyar, May 23, 2001, Google translation; Filipov, David and Yelena Nikolayeva, "Bonsai! Dwarf Trees Make It Big, The Moscow Times, April 19, 1995; "Kirill Sokolov,"; "Listening to the classics...," Bonsai Aesthetics, August 3, 2023; Tamara Belousova to RJB Facebook Messenger posts December 18, 2024, January 16 and 20, February 6, 8, 9 and 12, 2025; Tamara's Facebook page, which was started in Oct. 2015) SEE ALSO: Mar 21, Nov 22 |

||

| 27 |

1938 -- Warren Hill was born in Minneapolis, MN. [He would grow up in California

and be introduced to bonsai in 1960. After graduation from Moorpark College in Southern California, he would

teach horticulture and bonsai techniques for five years at this same school. He would be a member of the

California Bonsai Society, and serve in board

positions for the American Bonsai Society,

Descanso Bonsai Society, and the

National Bonsai Foundation in Washington, D.C. Beginning in 1970 he

would perform numerous demonstrations, lectures and workshops, his specialty being forest plantings.

Contributing articles for numerous publications would highlight not only his grasp of the art but his prowess as a

writer. Warren would be referred to as the "Father of

De-ionized Water" and would write extensively on this scientific

subject. From 1996 through 2001 he would be the second curator of the

National Bonsai and Penjing Museum.]

Warren Hill wiring a balsam fir (Abies balsamea) during his Windswept lecture in August 1983.

(Hill, Warren "The Concept and Reality of Windswept," ABS Bonsai Journal, Vol. 17, No. 3, Fall 1983, pg. 63)

Warren Hill with RJB at the National Bonsai and Penjing Museum,

("Profiles Of The Stars At IBC '94, Part II,"

Bonsai Magazine, BCI, Vol. XXXIII, No. 4, July/August 1994, pg.

16; "IBC Stars," Bonsai, BCI, Vol. XXVII, No. 2, March/April 1988; conversation

with RJB during the International Scholarly Symposium on Bonsai and Viewing

Stones, May 18, 2002, Washington, D.C.) SEE ALSO: Apr 1, Jun 10

Washington, D.C., July 1998 |

||

| 28 | 1974 -- Denver Bonsai Club teacher George T. Fukuma died at age 72. (SSN Master File by Birthdate; "George T. Fukuma," http://www.findagrave.com/cgi-bin/fg.cgi?page=gr&GSln=Fukuma&GSbyrel=in&GSdyrel=in&GSob=n&GRid=45087539&) SEE ALSO: Mar 18, Jul Also | ||

| 29 | |||

| 30 |

|